Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

WAR 1904-1905. FROM THE DIARY OF AN ARTIST

by Nikolai Samokish

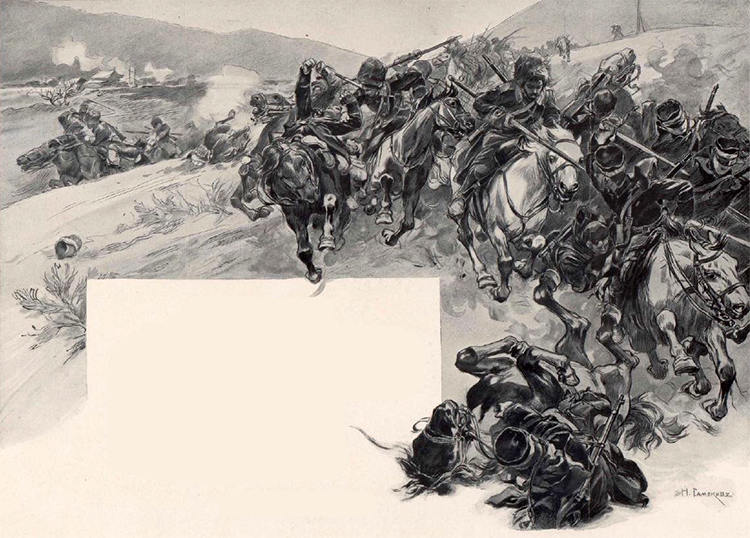

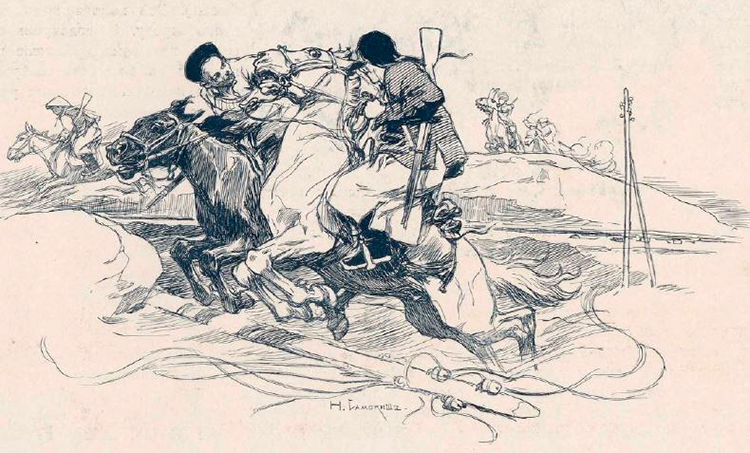

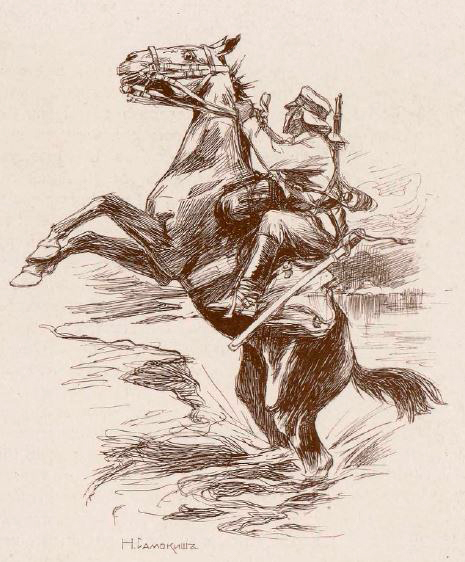

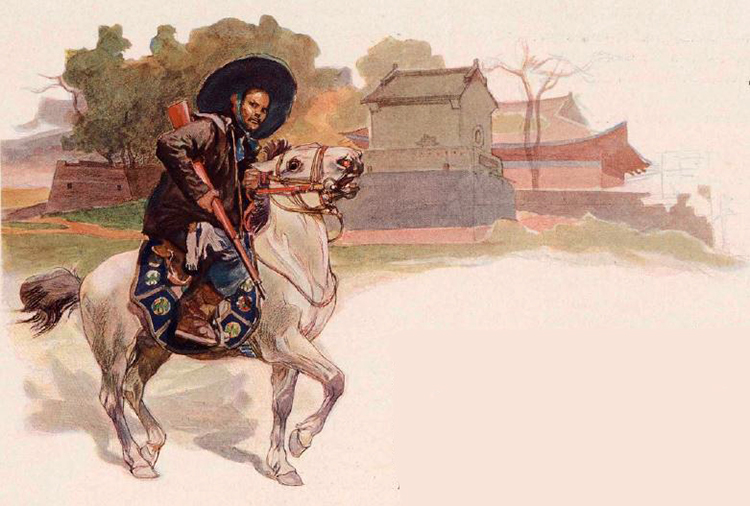

Sudden attack.

Foreword

Here I provide text excerpts from my diary and sketches from my trip to the Far East and my seven-month stay with the active army.

I beg the reader not to regard this text as a literary work; it is merely an explanation for the sketches, allowing a connection between various studies, sketches, and compositions on military themes that I created at the locations of our troops.

N. Samokish

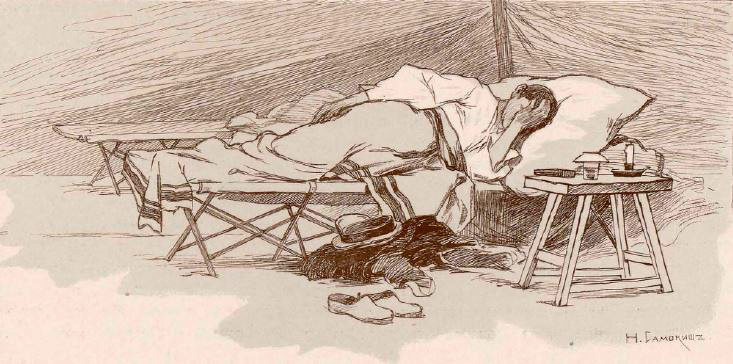

On the hill after the assault

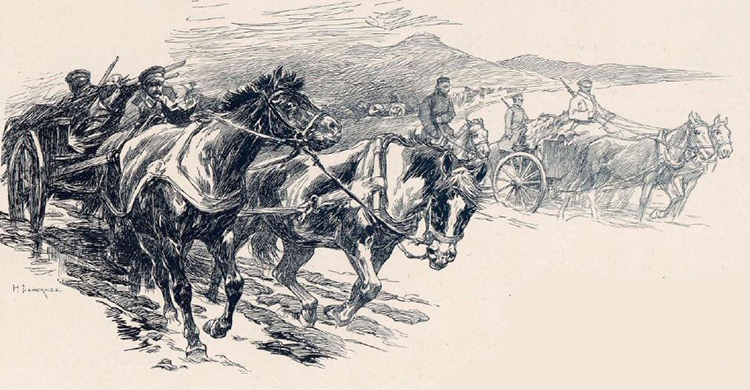

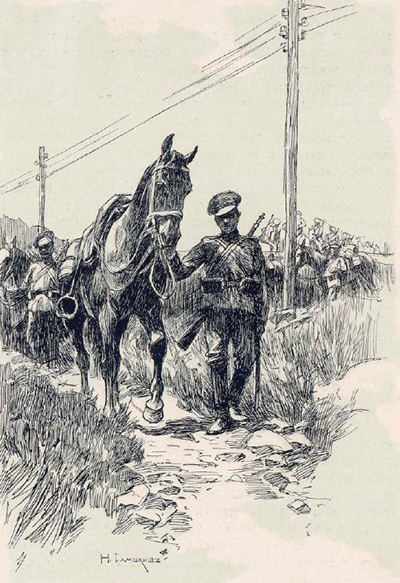

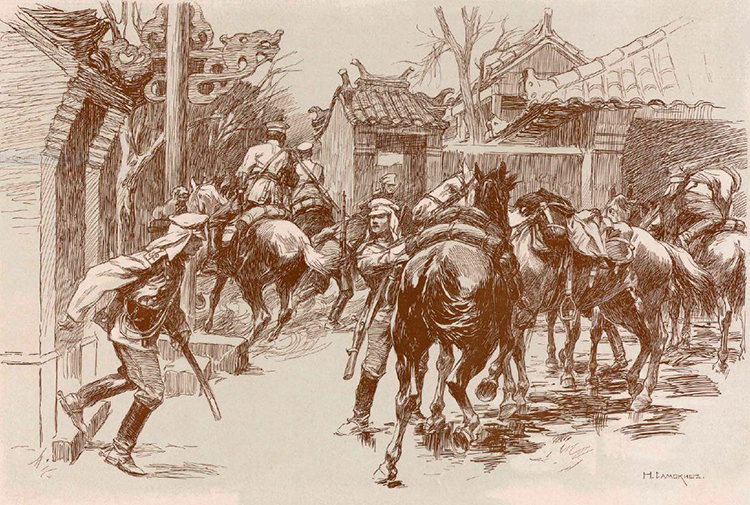

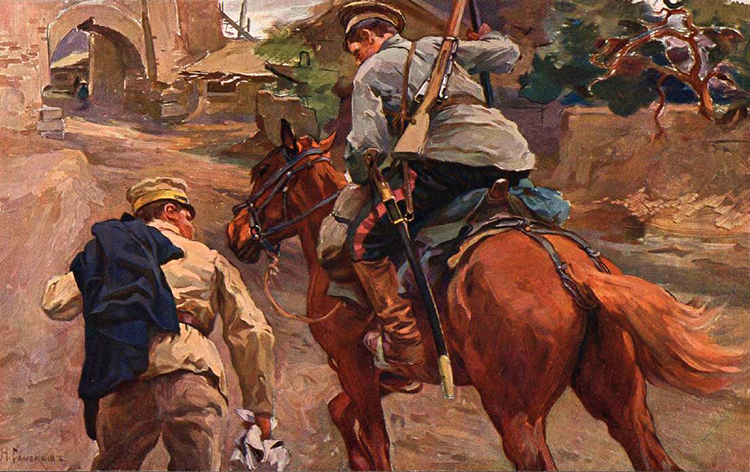

Pursuit

MY TRIP TO THE WAR

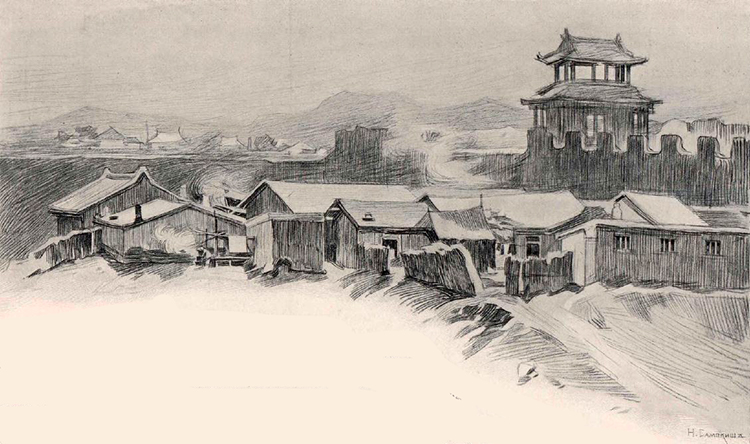

At the very outset of the war, naturally, I began to think that I should go. Besides personal motivation as a battle painter, the financial offers made to me as an artist played a significant role. Seeing the war as it truly was, not just in paintings, was a cherished dream. Unfortunately, my ongoing work commitments delayed me until mid-May, and only after brief preparations I could board the train; my Academy of Arts colleague Mazurovsky traveled with me. The journey was tedious, depriving me of the immediate transfer to the war zone. Finally, after three weeks of travel, I disembarked in Mukden. Although it was still far from the actual theater of war (our troops were near Wafangou), its proximity was keenly felt; I was overwhelmed by impressions: the landscape, the enchanting Mukden, our troops under the splendid sun—everything hit me at once and initially overwhelmed me with its novelty and grandeur; I looked around eagerly, unsure where to begin. Sometimes, I felt like sketching a marvelous shrine with its whimsical roofline against the dark blue sky; other times, our soldiers presented such an intriguing contrast against the backdrop of Chinese surroundings. In addition to all this, there were formalities to attend to: visits to the governor, who received me graciously and affectionately, meetings with his entourage, preparing the necessary paperwork, and obtaining an armband for unrestricted access to the front lines.

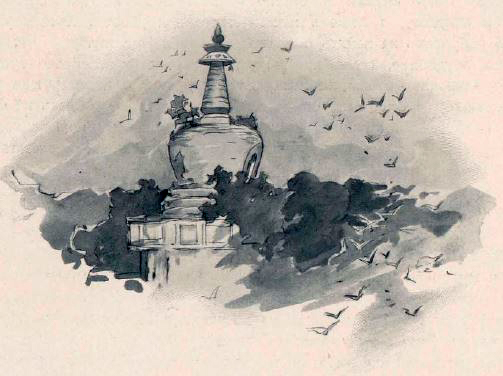

Finally, after a week-long stay in Mukden, everything was arranged, and I continued my journey to Liao-Yang , thinking I would soon reach the battlefields. Still, it wasn't easy: I had to wait and obtain further permits in Liao-Yang. Despite my eagerness to move forward, circumstances prevailed, and I had to establish my base in Liao-Yang—my place of residence—and travel from there to the troops. I was partly comforted that Liao-Yang was no less picturesque than Mukden, so my artistic enthusiasm found ample nourishment. With the assistance of my old acquaintance, General Chevalier-de-la-Serra, I quickly settled into a railway carriage he kindly offered me and began exploring the city, sketching and photographing everything that struck me as beautiful and picturesque. I began with the shrine of the "God of War," Liao-Miao (as befits a battle painter), and then worked all over the city. Still, my favorite spot for work was the extensive and extraordinarily beautiful shrine of Chang-Miao, situated on the outskirts near the city walls. Here I spent days.

One morning at the shrine, to my great pleasure, I found out that the headquarters of the 17th Corps had been established there. The corps commander, Baron Bilderling, knew me from my days as an Academy student and welcomed me warmly, allowing me to work within his Corps as I pleased.

I fully used his permission and visited Chang-Miao daily to sketch soldiers, cavalrymen, and artillery. Here, I also met the corps staff officers and young Count Keller, the son of the recently killed general.

The days were hot and tropical, and the light was so bright that I, accustomed to northern sunlight, was often dazzled by its brilliance and vivid colors. Ancient walls surrounded the city, and I sometimes climbed the parapets to sketch the city's surroundings, hills, and valleys. I attempted to paint the city streets several times, but the dust, rising in clouds and settling heavily on paint and paper, rendered my efforts futile.

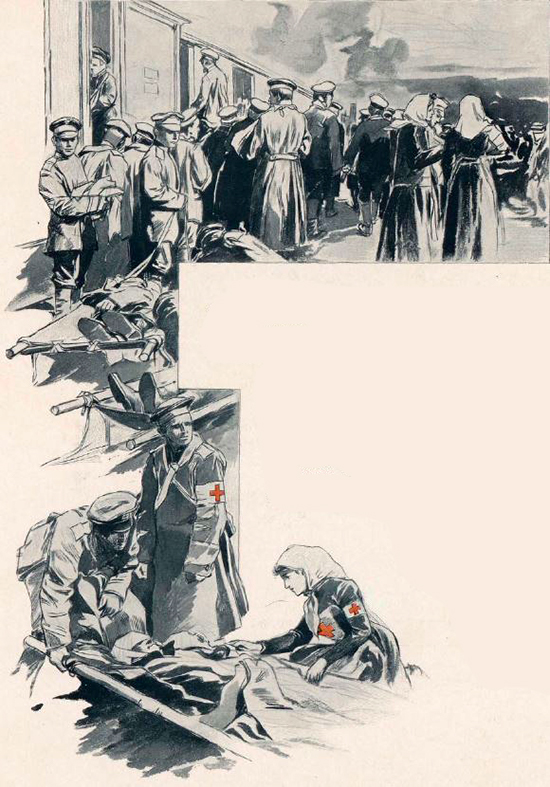

At the railway station, I often encountered trains filled with wounded soldiers, witnessing scenes of their transport to hospitals and barracks. Each of these trains reminded me that battles were being fought somewhere ahead while I was forced to sit and wait, when many unfolding events drew me to witness the action. I feared that everything would be over by the time I arrived, and I would miss anything of interest.

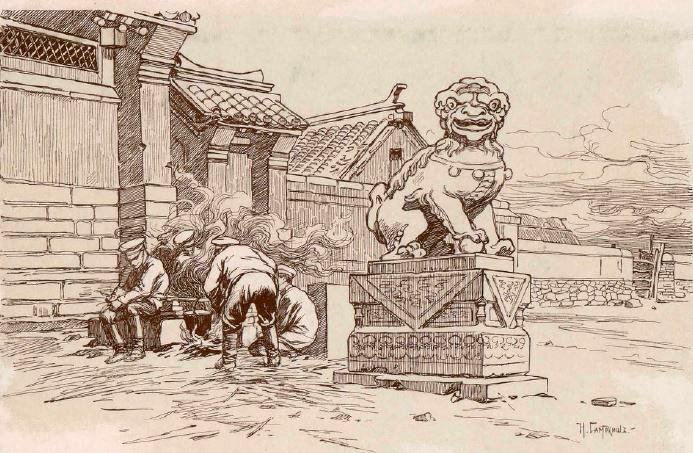

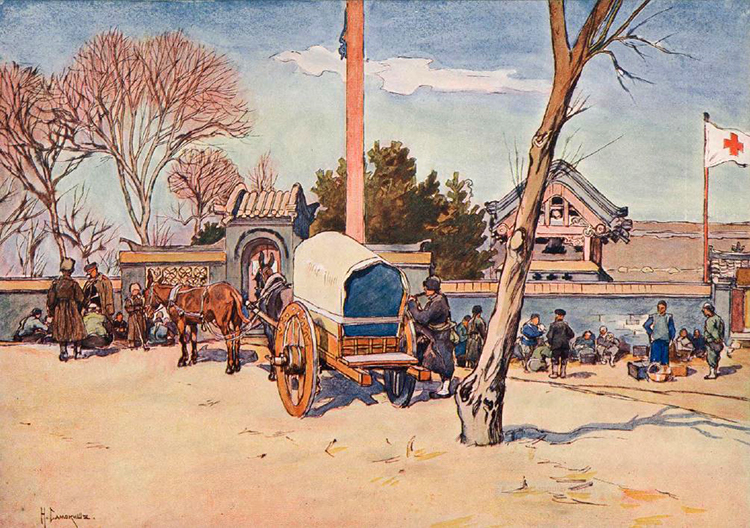

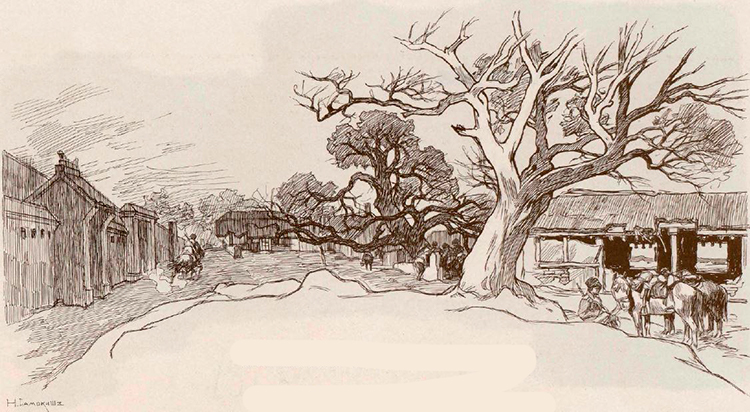

Street in Mukden

HAI-CHENG AND ASANDZHAN, JULY 1904

Hai-Cheng

I arrived in Liao-Yang from Mukden, thinking I would stay just a few days to get acquainted and, speaking in military terms, establish my base. However, things didn't go as planned. Firstly, finding accommodation proved daunting; thanks to the gracious General Chevalier-de-la-Serre, I secured a spot in a railway carriage. Secondly, I needed to sort through a pile of paperwork to travel to the active army, including arrangements for my staff and horses (which I didn't have). While dealing with all this, battles occurred at Wafangou and Dashichao, which I unfortunately missed. Instead, I vividly remember the dramatic impression made on me one summer evening when a train arrived carrying the wounded and dead from the battle of Dashichao.

The sun had already set, and the black silhouette of a huge locomotive stood at the station, emitting puffs of smoke and glowing with its fiery eyes. The crowd froze in anticipation. The doors of one of the carriages opened, revealing medics with red crosses on their sleeves, followed by orderlies, carrying a long figure wrapped in white from head to toe. The medics quietly lifted their sorrowful burden and carried it past the locomotive; the red light of the lanterns reflected off the head, shoulders, and feet of the motionless body. The crowd watched in silent and solemn reverence, devoutly uncovering their heads as the deceased passed. Behind these orderlies—more and more. A heavy and sorrowful spectacle!

That evening, I felt uneasy; the grim reality of war haunted me and painfully gripped my heart.

A few days later, after settling in completely, I decided to head towards the front lines of our army.

Our troops were at Hai-Cheng; I could reach there by railway since I still didn't have a horse. When all is said and done, I packed my paints, equipment, and a few belongings and set off.

The train arrived at Hai-Cheng in the evening, and my first concern was finding a place to spend the night.

Everything was overcrowded; there was no room at the station. I approached the station master, asking for assistance. He said his compartment had three people sleeping, and no other accommodation was available. "However," he added, "I'll give you good advice—if you want to find shelter, go to the Kursk Zemstvo community of the Red Cross, which is nearby by the station." I thanked him for the advice and went to the community along the roadside.

I entered a large tent with a tea table and saw two kind-looking nurses preparing tea.

Necessity makes a person bold and determined. After greeting them, I stated that I was seeking shelter. One of the nurses immediately went to fetch the officer in charge. A moment later, a tall gentleman with an exceptionally pleasant and kind face entered the tent. I introduced myself and received the warmest invitation. He presented me to the doctor and his assistant, who followed him. Everyone sat down to have tea. Two more wounded officers came into the tent, and the whole company engaged in lively conversation, naturally, revolving around the war. After tea, they showed me a spacious, well-set up tent and indicated where I could spend the night. The hospitality of these people always fills me with a deep sense of gratitude when I recall my time with them.

It was still light outside, and not feeling sleepy, I stepped out of the tent for some fresh air. At that moment, seven wounded men arrived from the front line; among them was one wounded in both arms by four bullets, but without any broken bones—he could move his arms freely. I offered him a cigarette, and as he smoked, he calmly told me how he had captured two mules from the enemy and was quite pleased with himself. One of the wounded brought in was in a serious condition and unconscious.

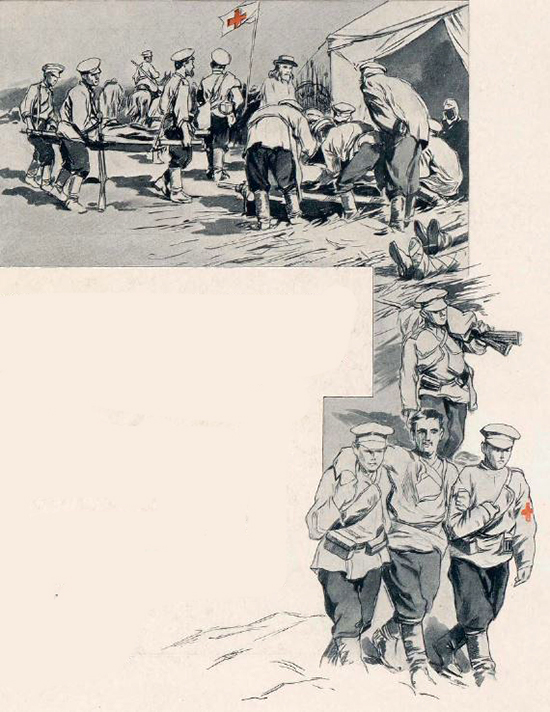

An experienced doctor quickly got to work with the help of the tender hands of compassionate and attentive nurses. He removed the initial bandages, cleaned the wounds with antiseptic, and applied fresh dressings. A bullet was removed, and within an hour, they were all lying in clean beds; the nurses fed and hydrated the poor, exhausted sufferers. I was moved by the care and attention the entire community staff showed towards the wounded.

After dinning, I returned to the tent. The night was warm, and I lay awake for a long time, listening to the sounds of footsteps and the rumble of wagons and artillery making nocturnal movements.

When I woke up—it was a beautiful morning. My kind hosts were still asleep, tired from their work the day before. I found a servant who had woken up and had him bring me some tea. Gathering my work materials, I set off through the town towards the distant hills where gunfire could be heard.

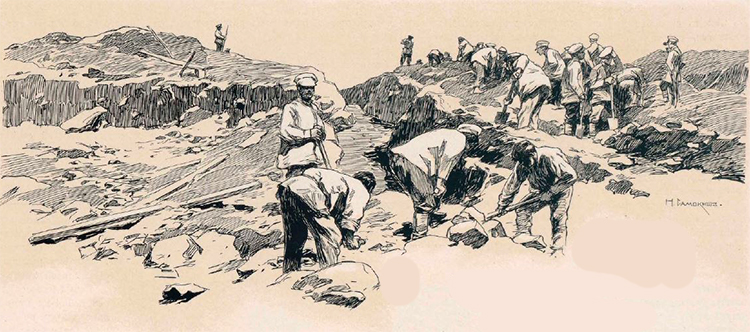

The July sun beat down intensely; I slowly climbed the hill where our soldiers were busy below. The path ascended higher and higher, and finally, I reached the summit. I saw sappers at work and a young, shirtless officer sitting under a Chinese red umbrella. A young man approached me, introduced himself, and was delighted to learn I was an artist. He presented me to the officer and hurried off to fetch another volunteer, his comrade, a student from the Odessa Drawing School. Both turned out to be very pleasant individuals, and I enjoyed conversing with them; subsequently, I met them several times again.

Having bid farewell to my new friends, I set off further towards the sounds of gunfire. The landscape was magnificent: towering cliffs, shades of burnt sienna with crooked pine trees in Chinese style, picturesque shrines on the rocks, and a dark blue sky. I wanted to sit down and sketch, but the heat was unbearable.

After walking another five kilometers, I reached the camp of the Morshansky Infantry Regiment. I was too exhausted to continue; a blister had developed on my foot from the long walk, making every step excruciating. Moreover, I was drenched in sweat, my clothes sticking uncomfortably to my body. Adding to this was the dust and an unquenchable thirst, making it impossible to proceed further.

I entered a dilapidated guardhouse where camp servants were preparing lunch for officers. I asked them to boil some water and offer me tea. I stripped completely, hanging all my clothes out to dry in the sun like Adam. While I drank tea seated on a campstool brought to me by a soldier, my dress and undergarments dried. Once dressed and rejuvenated, I felt ready to move on, but the sun was setting, and the distant cannonade had significantly diminished, occasional shots barely audible. Deciding it prudent to turn back, I set off for Hai-Cheng. It was a long way, and I arrived there in the evening after sunset. On that day, I walked about 30 kilometers under a 40-degree heat, which for me was a small portion if not for my blistered foot, which continued to bother me.

After recounting my adventures to my hospitable hosts and having dinner with them, I boarded a train to Liao-Yang to tend to my foot before my upcoming expeditions.

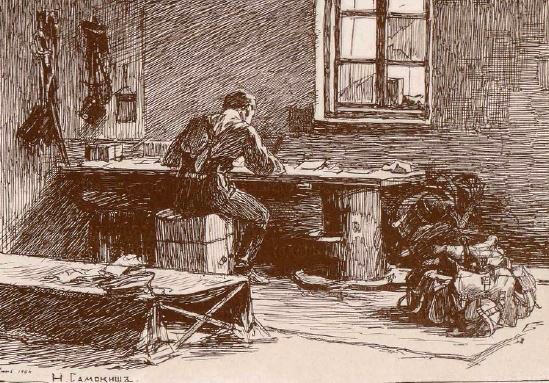

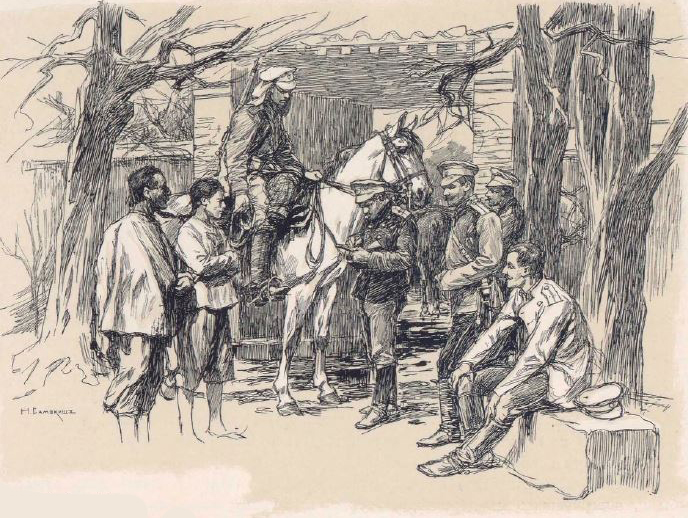

Urgent report

Asandzhan

Several days passed after my trip to Hai-Cheng, and my foot had almost healed, allowing me to walk freely.

Our troops retreated to Asandzhan. Again, I traveled by railway, but the weather had changed: it had been drizzling for two days, and everything was wet and gloomy. As I approached the station, I saw a crowd of drenched officers huddled under a shabby wooden shelter, among them my old acquaintance Demchinsky, a correspondent for a Moscow newspaper. Everyone was cramped under the leaky canopy, the station bustling with people. Cossack horses stood by the water pump, wet Cossacks huddled against the wall, a vivid and spirited scene. I wanted to photograph them; wading through knee-deep mud, I captured it all.

I left Liao-Yang in the morning without eating anything, feeling hunger pangs. I decided to grab a bite before heading towards the troop lines. Demchinsky was also keen on eating, but wanting was easier than getting: the crowd devoured everything, intercepting dishes on their way to us. Tired of waiting, I ventured into the kitchen, a very dirty and repulsive place, grabbed cutlets for myself and Demchinsky, and carried them under the shelter, barely finding a spot where water wasn't dripping. I had to stand since all the seats were taken. At that moment, the Commander-in-Chief emerged from his train in a gray coat, followed by some of his entourage in waterproof coats. A sample portion was brought to him, and he ate it right there in the rain. Then, walking along the carriages, he returned to his place. The rain gradually stopped, and I set off towards the troops, bivouacked one kilometer from Asandzhan. The road was awful: mud, puddles, and streams of muddy water. Slipping and falling, I climbed the slope and saw the camp under the sedge mats, soldiers lying under wet, sagging tents.

Everything seemed crowded and hidden away; in the distance, camp kitchens smoked. I walked along the camp and found a convenient place in an abandoned guardhouse to sit and paint a watercolor landscape, which was very interesting. The peaks vanished into the gray haze of mist and vapors; against this background, groups of trees and guardhouses stood out mysteriously, faintly outlined in delicate bluish-gray tones.

I worked for two hours and, finishing my work, headed to the station, afraid of missing the train since there was nowhere to spend the night, and besides Demchinsky, whom I met earlier, there was no one else. The trains were running chaotically: there was no schedule, so I had to watch for the moment; otherwise, I would have to wait indefinitely.

Finally, the train arrived, and a crowd rushed into the carriages, each to their place. Sitting in a relatively clean carriage after the mud and slush was pleasant. To my greatest pleasure, I met my old friend Krasnov, an officer of the Ataman regiment and correspondent for the "Russian Invalid" newspaper.

We settled into the same compartment, where several military men were already seated, and conversed cheerfully all the way, arriving unnoticed in Liao-Yang.

Arriving at the carriage where I lived, I immediately changed from my soaked dress, lay down, and fell fast asleep, tired and worn out from the rain.

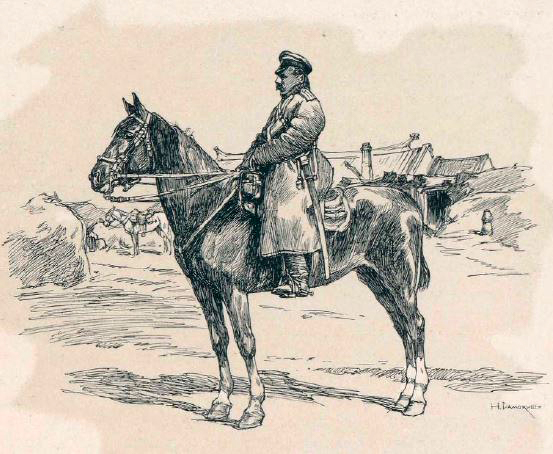

WITH DRAGOONS ON TAIDZYKHE

Upon hearing rumors of Japanese advances and anticipating major battles, I remained in Liao-Yang. I worked in the Chango-Miao temple, which, with its picturesque architecture and beautiful location, provided me with plenty of wonderful material for sketches and drawings. This temple also housed the headquarters of the 17th Corps, as I mentioned earlier. On August 6th, when I arrived at the temple, I missed the headquarters; they had set out early in the morning, leaving behind only the post of the flying post with two officers from the 52nd Nezhin Dragoon Regiment. Finding a suitable spot, I began my work. After a while, officers Cornets Kishkin and Troyanovsky approached me, introduced themselves, examined my work, and invited me for a cup of tea (a common courtesy in Manchuria). Over tea, we started a conversation, and I sketched a scene of the flying post quarters.

The young officers made a favorable impression on me, and I gladly visited my new acquaintances on the second and third days. On the fourth day, the squadron commander arrived to relieve the posts (replacing the 3rd with the 2nd squadron). I met Commander Kolomnin, who kindly invited me to visit the regiment stationed in the village of Quantun on the Taidzykhe River.

It is worth noting that even in Petersburg, I had dreamed of joining the Nezhin Dragoon Regiment; for some reason, it felt like home to me (I am from Nezhin, where I was educated in the local gymnasium). I was very pleased with the opportunity that seemed to fall into my lap, immediately agreed to the kind invitation, and hurried home. I quickly gathered my belongings (expecting to spend only 3-4 days in Quantun): my drawing supplies, camera, cloak, towel, and two handkerchiefs, and with this light baggage, I arrived at the temple.

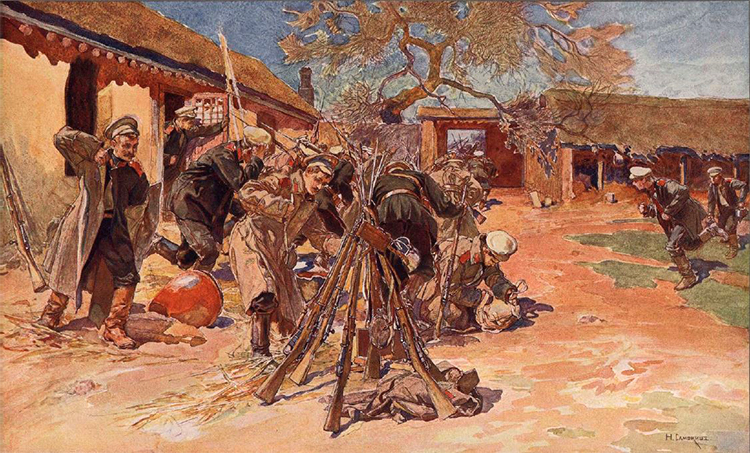

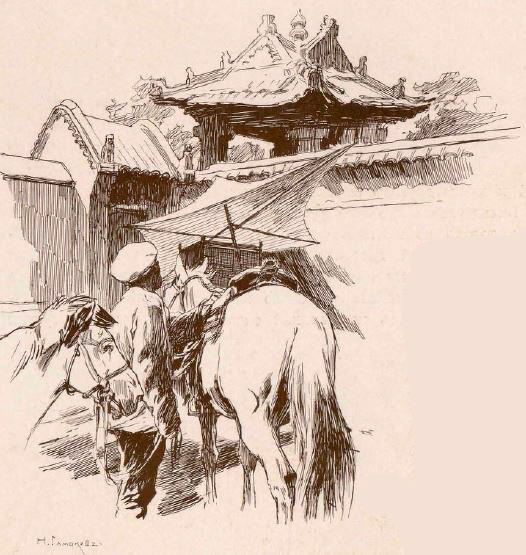

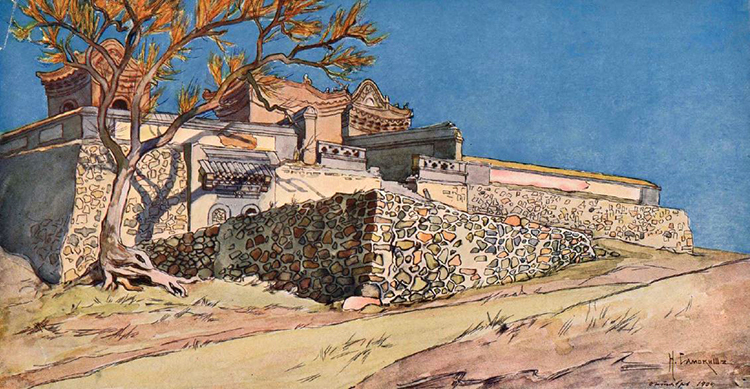

Chango-Miao Temple

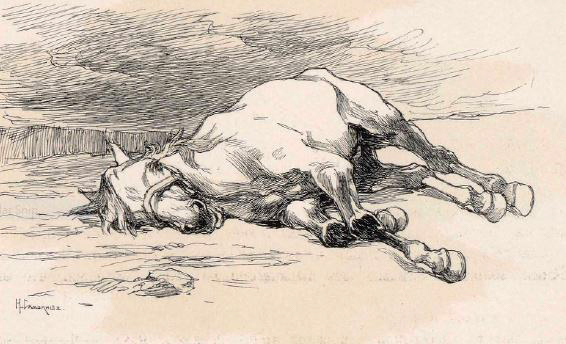

The dragoons had not yet set out; I took advantage of the time and sketched a sick horse lying in the middle of the courtyard, which was to be put down. At 4 o'clock, after lunch from the soldier's kettle, the platoon saddled up, and I was brought a white mare named "Isis," a kind and obedient animal, which I rode for many kilometers, and which carried me out of the fire under Sykvantun. Climbing onto the soldier's saddle, which is not particularly soft, I still felt a real cavalry horse beneath me and set off with great pleasure. We left the gates of Liao-Yang and followed the path of the posts, collecting units stationed at these posts, so our detachment grew larger as we moved forward. Having covered 20 kilometers, we turned off the road as darkness approached and stopped amidst a picturesque Chinese cemetery surrounded by trees. We immediately set up camp, pitched a tent for the officers, lit fires under the trees, tethered the horses, and made beds from saddles and saddlecloths. Tea boiled, and we all, lively and cheerful, crawled into the tent to sleep. Under the impression of the beginning of my campaign life, I could not fall asleep for a long time. The campfire beautifully illuminated the white dragoon horses. Weapons sparkled brightly under the trees, and in the mysterious twilight, dragoons wrapped in greatcoats lay on the ground. The silence of the night was interrupted only once by the hoofbeats: nearby, a rider galloped past, evidently with a report. Later, through my drowsiness, I heard the squadron commander rebuke the sentries, but I don't recall why.

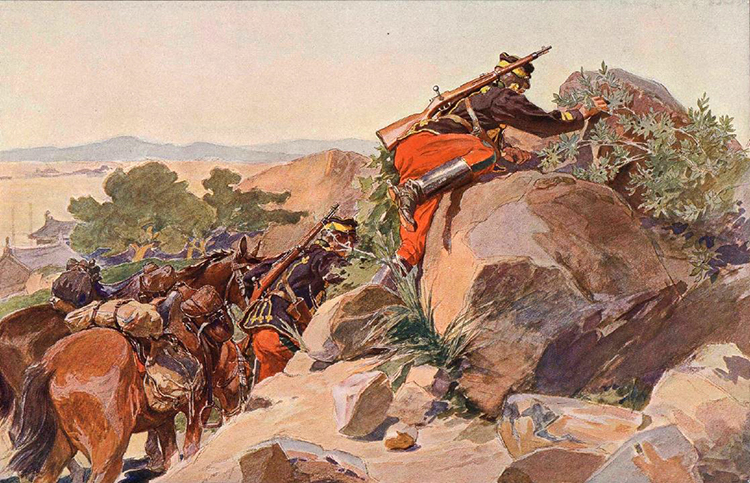

Japanese patrol

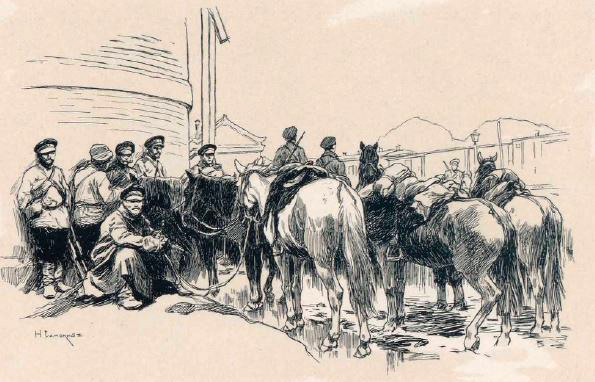

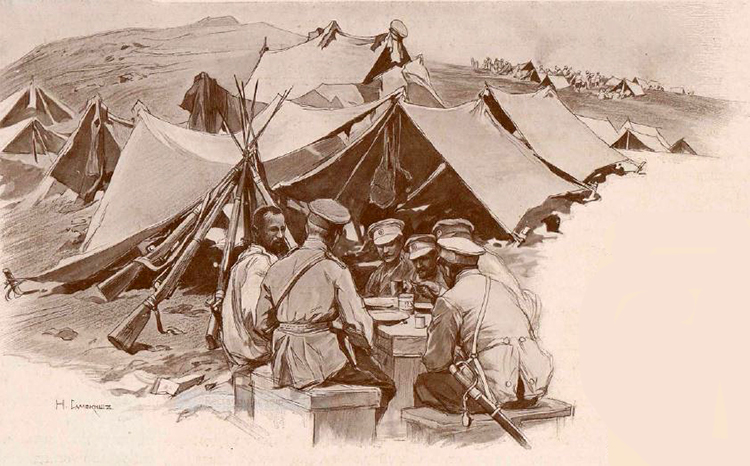

The Flying Post Quarters

When I woke up, a gray mist covered the entire landscape. The camp was already bustling; soldiers were cleaning the horses, and officers were still asleep. I took the opportunity to sketch our tent and the sleeping officers inside. After quickly drinking a glass of tea, we mounted our horses again and continued collecting posts and adding them to our squadron.

The road was in poor condition, with the clayey soil softened from recent rain. We constantly had to climb up and down, making riding on a road rutted with deep, water-filled holes difficult. Alongside the road were deep ditches, and beyond them stretched walls of gaolian, higher than a rider on horseback.

The squadron commander rode ahead on a splendid gray horse, followed immediately by me on my Isis, with officers and the squadron trailing along the road. A narrow path beside the ditch provided an opportunity to bypass a large puddle in the middle of the road; the squadron commander's horse, stepping with its front legs on the edge of the ditch, slipped into it, and its hind legs ended up in the puddle. I nearly followed the commander and managed to turn my horse and jump over the ditch. Stopping Isis, I saw that the squadron commander lay on his side under the horse, which thrashed in the mud, trying to stand up. I was just about to grab my camera to capture this incident when dragoons rushed in and ran to their commander, and in an instant, he and his horse were on their feet, though muddied.

Everything ended well, and neither the rider nor the horse suffered serious injuries. After this adventure, we continued our journey, and by 4 p.m., from a high hill, we saw the valley of the Taidzykhe River and the village of Quantun—our destination.

At first sight, as an artist, I already loved this area.

The magnificent panorama of the river, winding in a broad ribbon through the vast valley; all around were mountains with rocky cliffs, on which Chinese villages with their always picturesque temples nestled; all this, gilded by the evening sun, presented a wonderful, peaceful picture of nature, and I didn't want to believe that this river was already a front line, that beyond it everything was no longer ours, and that beyond this blue ribbon, one could not ride so freely and enjoy the beauty of nature, as your aesthetic pleasures could be interrupted by the prosaic crack of a shot and the whistle of a bullet, if not Japanese, then Hunhuz.

Our squadron entered the street and started making its way through the houses. When we reached one of the larger houses, a dragoon told me it was allocated for our commander and his officers, while the neighboring houses were for the men of the 3rd squadron. I gladly dismounted in the courtyard of our house from my Izida; a whole day of riding had taken its toll on my legs, and I made my way into the house with difficulty. The village house, although not luxurious, was quite spacious and cozy.

In the house, we were greeted by a handsome officer of Eastern descent, Colonel Mirza-Ali-Guli, around 50 years old. He warmly welcomed us and invited us to share the space with him. I settled into my corner on the mat and made myself comfortable.

The next day, Lieutenant Colonel Mirbach, one of the officers, invited me to the officers' common dining room organized in the regiment.

Lieutenant Colonel Mirbach

My housemates and I left around noon to go to the dining room.

We passed through the square, in the middle of which was a small temple housing the regimental commander's apartment.

The large house, neatly arranged and furnished with tables and benches in two rows, served as the common officers' dining room. The kitchen was located to the side of the entrance.

I was introduced to the regimental commander, Colonel Stakhovich, who kindly offered me a seat near him and introduced me to the other officers of the regiment. The lunch was very delicious, and one had to marvel at the organizational ability of Lieutenant Colonel Mirbach, who managed to arrange such a splendid dining room amidst the wartime conditions. After lunch, we had tea and engaged in a lively conversation about the war and our situation, given the enemy, but it all seemed distant. No one suspected we would face the Japanese up close in a few days.

The next day, I take my camera and inspect the area. Choosing subjects for studies was not difficult: everything was picturesque and beautiful, colors glowing under the splendid August sun of Manchuria. I took several interesting scenes, returned home, grabbed my box of paints, and headed to the rocky cliff overlooking the beautiful valley of Taidzykhe and the gorges of the mountains. After completing my study, I returned to the village around noon and went to have lunch. During lunch, the regimental commander criticized me for going alone to work far from the village and warned me not to trust the apparent calm. He already had information about the enemy's movements. I continued to go to study daily, forgetting the warning, and after a few days, I was already thinking of going back, especially since my photographic films were running out. But Lieutenant Colonel Mirbach came to my rescue, kindly offering his camera and films; I was very pleased and grateful to him for this kind favor.

After receiving the films, I postponed my departure indefinitely, as life was good here for me, and the scenery was wonderful for studying. A few days later, Brigadier General Stepanov arrived at the regiment, to whom I had letters of recommendation; he kindly welcomed me, sitting with his adjutants in the courtyard of the house, and treated me to candied fruits (a rare delicacy on the campaign trail).

Soon after the general's arrival, Colonel Stakhovich celebrated 20 years of service in officer ranks; I was invited to a grand dinner with fried meat. A huge bonfire was lit in the courtyard of the dining house, and fried meat skewers were roasting in the officers' presence. Against the evening backdrop of the warm Manchurian sky, it was a beautiful scene of campaign life. The gracious host, the initiator of the celebration, entertained the guests, speeches were made, and toasts were proclaimed; time passed unnoticed, and we bid farewell and went to sleep in our houses.

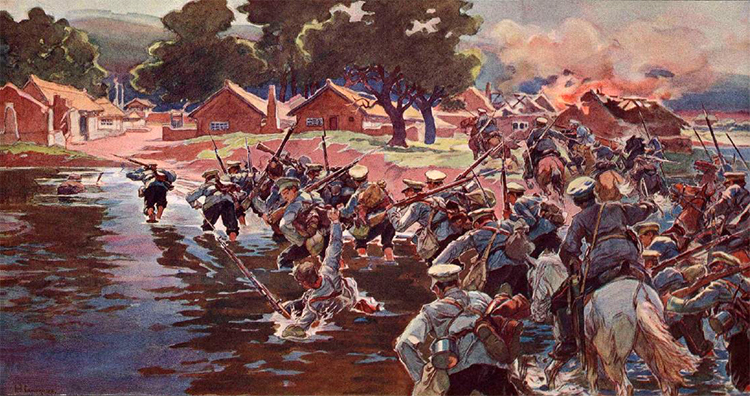

During all this time, the regiment actively performed guard duty along the banks of Taidzykhe, sending out reinforced patrols and making trips with larger detachments to the opposite shore, where the enemy was expected. The crossing was not easy: due to the rains, the river level had risen, and both men and horses had to exert a lot of effort to deal with the fast and deep current.

The young officers, my housemates, willingly went on reconnaissance. Day by day, alarming reports began to appear that patrols were encountering the enemy; one patrol reported being fired upon, but everything proceeded as usual; several horses were wounded, but all the men were safe. In one of the distant patrols, my housemate, the young officer T., went out. A dragoon galloped up to me the next day with a note from T. He wrote: "Nikolai Semenovich, come to me with a dragoon. The landscape here is marvelous."

At that time, I was working on a very interesting study and decided to go the next day, writing a note that I would be there tomorrow. The dragoon rode off, and I calmly finished my work and returned to the house, where refreshing tea awaited me, without which one cannot exist in Manchuria: it refreshes and warms. We sat, smoked, and talked peacefully about our distant homeland. Mirza-Ali-Guli showed portraits of his dear little children, whose photographs he had just received via the flying post. Outside, the fire crackled cheerfully, the men prepared a simple dinner, and the Chinese, our hosts, stood at the doors and looked at us with curiosity, unabashedly chatting and expressing their opinions about us; their children boldly approached us and touched various items lying in the house.

The appearance of Cornet T., who returned from reconnaissance very excited and, without saying anything to us, went to report to the regimental commander, was completely unexpected. We all became alert; something alarming happened; the Chinese disappeared somewhere, and everyone's faces became serious. Half an hour later, T. returned and reported the commander's order to saddle the horses, pack mules, and be ready for immediate re-deployment. It turned out that above Quantun, about 35 kilometers away, the Japanese had already begun to cross Taidzykhe using pontoons laid overnight. A battalion-sized infantry unit was already on this side. Our regiment was the outermost point of our advanced guard, and therefore, if not tonight, then tomorrow, it had to come into conflict with the enemy; lacking infantry or artillery, it could not interfere with the crossing, let alone engage in battle with the enemy's superior forces. It was decided to wait until morning and slowly withdraw, observing the enemy.

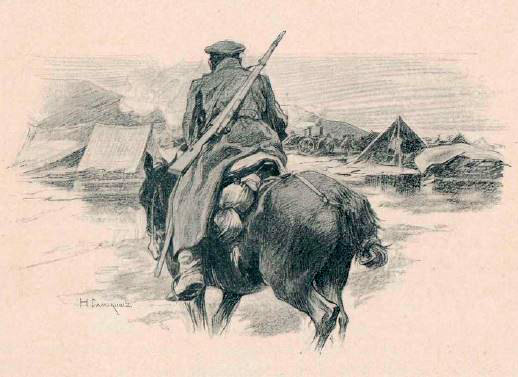

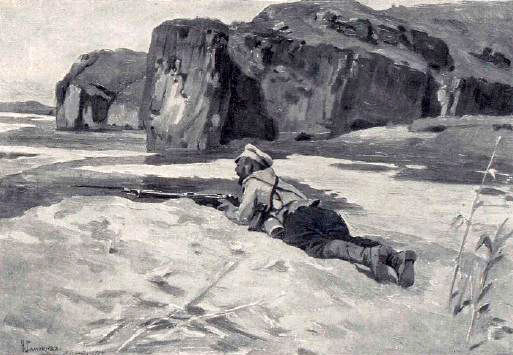

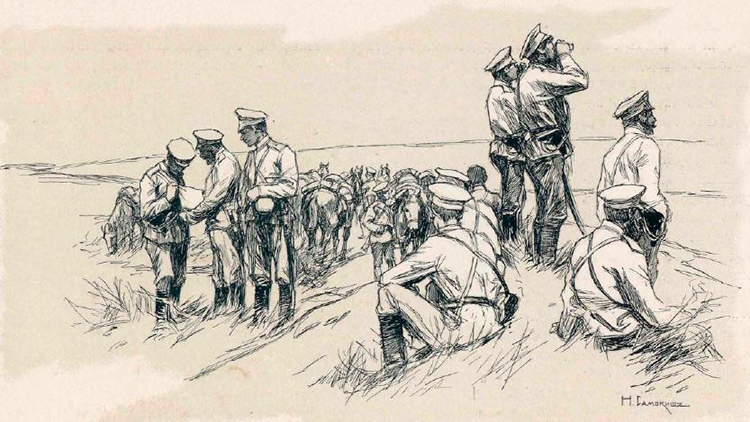

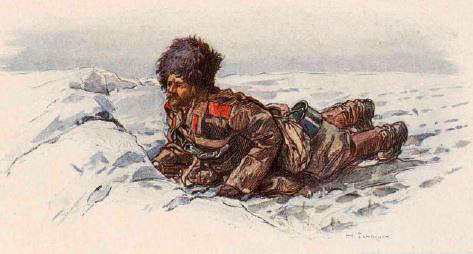

Bank of Taidzykhe. A marksman of the hunting squad watches the Japanese.

I went out into the yard; in the nighttime silence, the commands and the footsteps of the reinforced patrols sent out that night throughout the village and along the riverbank echoed particularly solemnly. The yards were filled with the bustling of dragoons saddling their horses and the fuss of orderlies with the officers' packs. It's unlikely anyone could sleep peacefully, but I lay down; I thought I wouldn't fall asleep, but I did, and very soundly. I woke up to the noise in the yard; it was already quite light: a light mist was rising from the Taizi River, and the dragoons of the 3rd squadron were lining up along the street. The officers' horses stood by the temple, and dragoons with reports constantly arrived. The regimental commander came out with General Stepanov. They brought out the standard, and a platoon, commanded by cornet T., took it and slowly rode out of the village with a convoy that had been sent ahead moving in front.

I admired this calm activity of people who had the enemy at their backs. Seeing that my 3rd squadron was leaving, I mounted my Isida and joined the squadron. About eight kilometers in, the regimental commander overtook us with his orderlies, and shortly after, an order was given to stop.

We stopped on the bank of the Taidzykhe, which descended steeply. The dragoons of the 3rd squadron dismounted and settled under the cover of sorghum, and the other squadrons gathered around an elevated point on the bank. The last squadron had not yet left the village when a man from the other side of the river swam across. We saw a crowd of Chinese from the village running to the riverbank where the Japanese man had come ashore; he was immediately dressed in clothes brought by the Chinese and mixed with the crowd that returned to the village. Our patrols in the village reported that the Chinese were signaling the Japanese about our regiment's departure and had captured one signalman. He confessed that he had been giving the Japanese directions on which way our regiment retreated. The commander and senior officers climbed the rock and carefully examined the surrounding area and the opposite riverbank with binoculars. A dismounted platoon of dragoons lay on the rocky ridge. The sun was very hot; it was already around 10 a.m. The enemy's low-lying shore was as clear as day. About two hundred meters from the shore, littered with small whitish stones, was a large village with a grove and the inevitable sorghum, and beyond it, hills rose like waves of the sea, becoming almost blue on the horizon from green-yellow.

"Your Honor, look straight ahead, under that tree standing alone," I heard the dragoon's voice nearest to me. I directed my binoculars in the indicated direction and, at first, couldn't make anything out; there stood a tree casting a round shadow on the grass. I asked the soldier what he saw; he said a Japanese sentry was standing under the tree. I focused my binoculars again and now saw a motionless figure in yellow khaki, leaning on a rifle in a cap with a neck flap. For five minutes, I watched him without seeing any movement. Continuing my observations, I saw another similar figure cautiously crawling up to the first one along a ditch; evidently, it was a junior sentry. A few minutes later, the junior sentry crawled back, having received or passed on some orders, and the sentry remained in the same position. Tired of watching the motionless Japanese, I carefully crawled back so as not to reveal our position and, descending from the hill, wandered among the squadrons. The groups of dragoons and horses were very picturesque; assigned scouts constantly departed and disappeared in different directions. After walking around and taking some photographs, I climbed the hill again; it was around noon, and everything stood out clearly against the sandy shore; the sentry was still standing under the tree but had moved along with its shadow. A slight movement became noticeable in the still sorghum; a mounted figure flashed by on the village street; everyone became alert; the figure reappeared and stopped in the shadow of a farmhouse, making it difficult to discern; all binoculars were directed at that spot. A few minutes later, the rider emerged from the shadow cast by the farmhouse, appeared in the bright sunlight, and slowly rode along the street leading to the riverbank, carefully observing our side; the rider was getting closer and closer; my heart pounded like a hunter's when the big game comes within shooting range.

The dragoons impatiently looked at the command, awaiting orders, but there were none... everyone was watching...

He was riding a dark bay horse, dressed in yellow khaki pants, a cap with a neck flap, a rifle slung over his shoulder, and a steel saber at his waist. His face was indistinguishable, hidden by the shadow of his cap visor. Slowly, he rode to the end of the street and emerged onto the shore, no more than 1200 steps from us, all the details of his equipment visible.

The dragoons asked for permission to shoot — finally, they aimed... the command came to fire, and a volley of bullets rained down on the other side.

The horse reared up and, turning towards the village, galloped away at full speed; the rider clung tightly to the saddle, hiding his head behind the horse's neck and convulsively jerking his hands: he was wounded; 2-3 more volleys followed; we could see the bullets hitting the water and the shore, raising splashes and dust. Everything disappeared in the sorghum, and an order was given to fire several volleys at the village, assuming hidden enemy forces occupied it.

Alarm

After waiting some time, I descended from the hill again and joined my 3rd squadron. Then, the regiment moved out, leaving a lookout post behind. We walked along a country road for quite a while, taking all necessary precautions; by evening, we reached a village (I don't remember the name) where we settled for the night.

I stayed in a farmhouse with the regimental doctor. Nearby was a temple. The regimental commander, Stakhovich, settled in the small bell tower, and the standard was also placed there. In the evening, we heard the thunder of the Liao-Yang battle for the first time. The horses were not unsaddled; their girths were loosened, and they were left ready for immediate departure.

Exhausted by the march and the day's impressions, I slept like a log. I woke up early; my body was itching terribly: it turned out there were masses of bedbugs. I slept soundly only because of fatigue. Otherwise, sleeping with these myriad foul-smelling insects would have been impossible. Going out into the yard and washing up, I peeked through the farmhouse wall and saw our commander, who, sitting in his bell tower, was cheerfully nodding at me, inviting me for tea. I hurried to him and started drinking tea; the commander hadn't slept all night, receiving reports and sending out scouts.

The morning was wonderful; in the distance, on the hills towards Liao-Yang , artillery roared, and bursts of shrapnel were visible. Brigadier General Stepanov slept under a canopy at the temple beside his adjutants. His orderly had hung his weapons and clothes on a small, gnarled pine tree, it looked like a military Christmas tree, where, instead of sweets and bonbonnieres, hung a revolver, saber, gloves, trousers, cap, and other items of the officer's wardrobe. The general woke up and began to dress. After tea, everyone went to the wall of the ruined temple to observe the Liao-Yang battle from there. The artillery roar grew louder, turning into a continuous rumble. The general and his entourage presented an interesting picture, sitting and standing on the temple wall. After walking around the village and the squadrons' positions, I returned home and began to draw. The day passed peacefully. The evening was dark, a thunderstorm was gathering, and against the black backdrop of the sky and hills, the flashes of artillery fire at Liao-Yang sparkled like lightning. A fierce battle was underway. Sleep was elusive, but everyone gradually lay down, taking all possible precautions. I couldn't sleep: the bedbugs and the artillery roar made me involuntarily listen to everything happening around me.

A noise erupted in the street, the sound of footsteps and shouting: "Catch him, catch him!" I rushed out; it was dark, nothing was visible, only the sound of pursuit along the street, and then everything fell silent. I went to the temple, where the situation was explained. A suspicious Chinese man had been detained in the evening and placed against a wall with a guard assigned to him; taking advantage of the darkness, the Chinese man attacked the dragoon, and before the latter could stab him with his bayonet, he pushed the dragoon aside with a strong shove and disappeared into the darkness. The dragoon couldn't shoot, fearing he might hit our men, so he chased after him but, of course, couldn't catch him as the Chinese man vanished into the sorghum field.

Chinese spies

The crack and roar over Liao-Yang kept growing louder... there was no time for sleep...

The restless night passed; dawn broke, and with it came the enemy. I had just drunk a glass of tea and stepped out onto the street, already bathed in the first rays of the sun, when I saw three dragoons galloping in at full speed, with a stream of bright red blood flowing down the backsides of one of their white horses. At first, I thought the horse was wounded, but it turned out the dragoon was wounded in the soft part, and his blood had stained the horse's haunches. The commander immediately ordered the 2nd squadron to go beyond the village and hold back the enemy's advance. The rest of the squadrons quickly assembled and began moving out from the village streets onto the road; all this happened within 10-15 minutes. The last men had barely left the village when we heard volleys of rifle fire. Our 2nd squadron had encountered enemy infantry and engaged them. Not knowing how many enemy forces had arrived and not wanting to be attacked from the rear and flanks, the commander ordered a retreat at a trot. The squadrons moved out in perfect order on command: "Trot, march!" the dragoons swayed rhythmically in their saddles, raising dust clouds. After traveling about six kilometers, they slowed their pace, went for a walk, and finally stopped. At this time, the 2nd squadron, returning from the battle, joined us; there were a few wounded, but the horses suffered more.

After retreating another three kilometers and passing a large village, the squadrons emerged onto a vast field planted with beans and surrounded by sorghum; the men dismounted and lay down wherever they could. The sun was already low, and the evening was quite cool.

Here, a very touching episode occurred.

In the battle, a horse from the 2nd squadron had been severely wounded; it had to be left on the battlefield. Three hours had passed since the squadrons had been lying in the sorghum when suddenly, that horse, barely moving its legs, came to the field and headed straight for its squadron, staggering, stopped in front of its comrades, and then collapsing to the ground, died a few minutes later.

I witnessed this scene, which moved everyone around to tears; on their faces, one could see pity and amazement at the instinct of this noble animal, which came to die in its familiar squadron. The dragoons stood around in silent sorrow. Twilight fell; it was cold and wet from the abundant dew on the bean plants and sorghum. Prince Orbeliani, the head of the Caucasian brigade, arrived, along with Plautin, the commander of the Terek-Kuban regiment. A military council was convened, and it was decided to move at night to ascertain the enemy's strength. Lying on a burka, Prince Orbeliani and the officers around him spoke in half-whispers about the upcoming raid; the approaching night added a sense of mystery to this meeting and to the dark figures of the people gathered around the dim lantern, where a map of the area lay.

Campfires were prohibited, and the men were ordered to maintain complete silence. When the council ended, it was decided to send the standard with a platoon of dragoons and a small convoy that had been with the regiment and to go to the enemy's location at night. The regimental commander called me over and said that, given the extreme risk of the night's mission, he asked me to go with the standard to the regimental convoy stationed in the village of Sykvantun. Exhausted by the day's events and feeling an overwhelming desire to sleep, as I hadn't slept at all the previous night, I readily agreed to his proposal, especially since my young friends, Cornets Kishkin and Troyanovsky and Lieutenant Colonel Mirbach had approached me, urging me to go to the convoy to get some rest and then rejoin the regiment. I thanked them for their concern and, mounting my Isida, joined the standard platoon. The regimental doctor persuaded me to go with him, and we left the regiment behind, waiting for 2 a.m., the appointed time to march.

Parting with the regiment and the dear officers who had warmly welcomed and sheltered me with true hospitality, I thought I was leaving them for 2-3 days, but it turned out differently: I wouldn't see my friends for a long time.

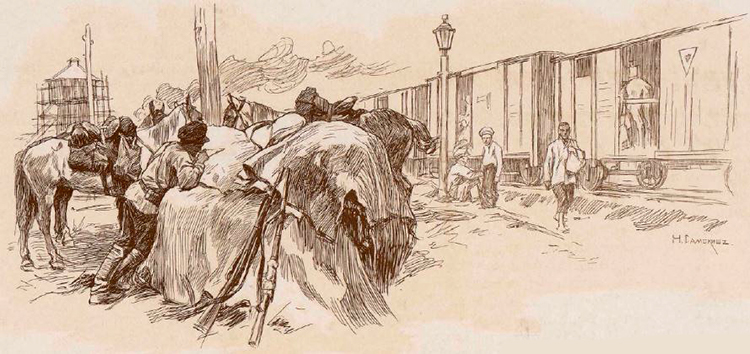

Shahe. Battle at the railway station

THE ACTION AT SYKVANTUN

Taking my horse Isida from the groom, I mounted it and joined the platoon of dragoons with the standard, waiting for the signal to move out; at that moment, the regimental doctor and veterinarian rode up to me and suggested I go with them along with the doctor of the Dagestan regiment and an escort of 10 Dagestani riders. The doctors said they were taking the shortest route. I gladly joined them, especially since the doctor of the Nezhinsky Dragoon regiment was very pleasant, making his company enjoyable.

We said goodbye to the commander and officers of the Nezhinsky regiment, wished them success, and slowly moved off, making our way through the sorghum. Accompanying us was the doctor's cart, pulled by a pair of horses. I placed my small baggage on this cart. It was around 2 a.m. and quite bright; the road ran close to the bank of the Taizi River; on the other bank, hills rose steeply. The cannonade of Liao-Yang was audible.

The doctor of the Dagestan regiment took it upon himself to be the guide, constantly checking his compass, and rode ahead.

The village of Sykvantun, where we were headed, was only six kilometers away; we expected to be there in an hour or an hour and a half and could still get some sleep before morning.

But an hour passed, then another; we trustingly followed the doctor, with the escort riding behind us and our cart struggling along the terrible road. Gradually, we began to doubt the doctor's navigational skills. He reluctantly answered our questions about how soon we would arrive and kept checking his compass.

Another hour passed; we entered a village, but that was not Sykvantun. Before this village, our cart hopelessly got stuck, and one of the horses fell. All efforts to lift the horse and move the cart were in vain, so we decided to abandon the cart and move on. Holding it on the front pommel of the saddle, I took my bundle and rode with the others into the village. Here, it was admitted that a mistake had been made to go in that direction.

We were beside ourselves with frustration due to fatigue, the cold night, and the prospect of having to ride for several more hours. Our horses were visibly tired, too. We decided to find a Chinese guide, but that was no easy task.

The village was asleep, not a soul in sight, and its inhabitants might have abandoned it. We approached a large home, dismounted, and climbed over the gate. Dogs attacked us, but there was no sign of any living person; they knocked on the door with a rifle butts—no response. They decided to break a window.

The light frame cracked, and at that moment, the head of a Chinese man, quite elderly and having watched us for some time, appeared.

They took him out, and after 10 minutes of futile conversation, during which neither side understood the other, they brought the Chinese man out to the street, repeating the word "Sykvantun." Finally, the Chinese man pretended to understand and started walking ahead, pointing into the distance. The group followed him down the street, turned a corner, and found themselves on a narrow path in the sorghum field. Everyone lined up in a single file, with the Chinese man in front. I was third at the head of our detachment. It hadn't been 10 minutes before the front stopped at a ravine, and the Chinese man disappeared without a trace.

The situation was dire: the Japanese could be close, and the Chinese man could have warned them.

Dawn was breaking, and the hills were becoming more clearly outlined against the whitening sky.

What to do? Uncertainty about where we were and what awaited us made us decide to wait for full daylight, especially since the doctor declared he wouldn't risk continuing and getting captured with the convoy.

We moved to a drier clearing where the millet had already been harvested; a road led through the clearing, but to where was unknown.

It became fully light; the morning was beautiful, though cold. Our detachment settled down haphazardly without unsaddling the horses; many immediately fell asleep, holding the reins in their hands.

I couldn't sleep; it was too beautiful. I dismounted from Isida, loosened the girths to let the poor animal rest a little, unbridled her, and tied her with a lead rope to a stump. Then I went to pick sorghum heads for Isida.

After feeding the horse, I walked down the road towards the hills, thinking of surveying the area from above. I had not gone 200 steps when our troops appeared around a roadside bend. It was an infantry regiment heading to Sykvantun; the regimental commander and his adjutant rode in a carriage at the front. The sleepy, haggard faces indicated that the regiment had marched all night.

Against the backdrop of the early morning, the gray, irregular line of soldiers with pack mules and mounted officers slowly crawling along the muddy road was very picturesque. I hurried to take several photographs of the passing regiment. From questioning, it turned out that the village was not far away, and we, having broken camp, set off by the shortest route to the visible Sykvantun.

When we entered the street and reached the square, the sun was already high, and the Nezhinsky Dragoon regiment's convoy stood among the trees near the houses.

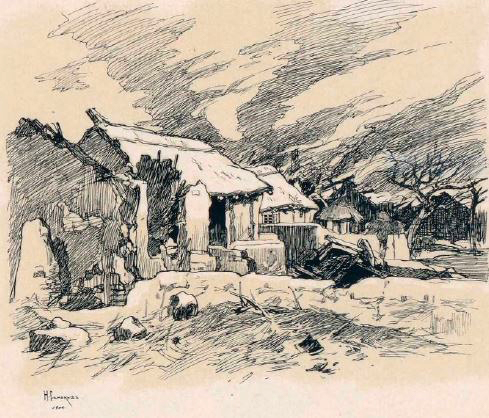

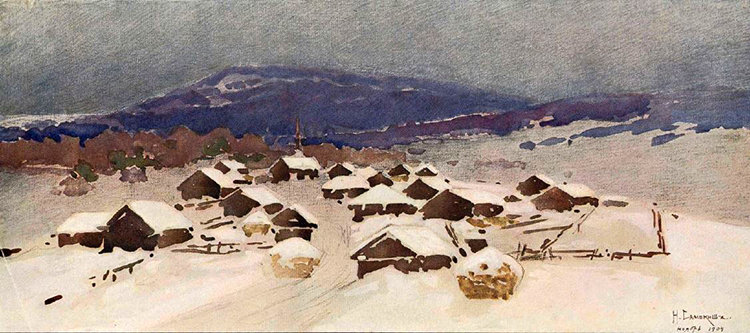

Village of Sanlinzi near Changsamutun

Several tents were in the neighboring yard; the convoy commander and the priest lived in one of them, and a supply officer in another. We got acquainted and started drinking tea, which seemed extraordinarily delicious, as I had drunk or eaten almost nothing for nearly a day.

After drinking numerous glasses of tea and eating whatever God provided, I felt a surge of vigor and energy. Thanking our hospitable hosts, I went to explore the village.

A main road ran through the whole settlement. On one side was a ridge of hills, and about two miles from the village rose a separate hill with a small elevation on the top (later named the hill with the navel).

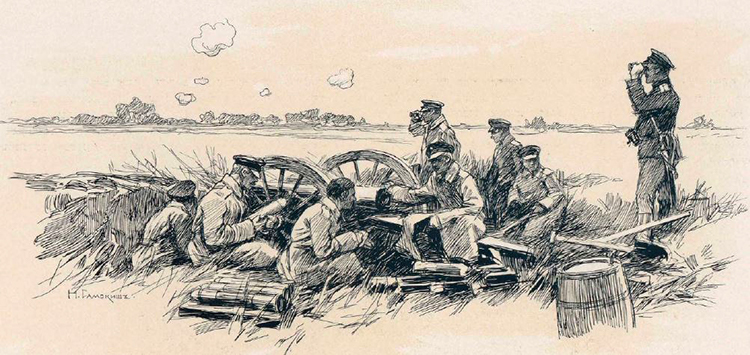

It was a beautiful August day. The sky was cloudless, and the sun was warm. Upon leaving the village, I saw shrapnel clouds on the horizon and heard distant cannon fire, but I had grown accustomed to this daily concert and paid little attention to it. I moved along the road towards the hill to survey the surroundings from its summit. It was hot; as I approached, I heard the artillery fire more clearly, discerned our trenches and troops covering the hill, and the guns became visible.

Judging by the number of troops, it became clear that I was at an important point in our position. My interest doubled when I saw a group of military men surveying the hill. A general's pennant fluttering on a spear was visible among the convoy.

The shrapnel clouds seemed closer and clearer. Our guns had not yet fired, but they were preparing for a volley. The general appeared near the guns, and the battery commander approached him; a minute later, the commander returned to the guns. The general and his entourage climbed higher. The infantry moved to the right, and behind them were seen the ammunition wagons stretching in a long line, starting almost from the village to the hill.

Suddenly, something hit and thundered very close. I quickly turned around—it was a volley from our battery; light dust before the guns indicated they had just sent their greetings to the enemy. The crew bustled for a few seconds, reloading the guns, and then everything froze in place; the general appeared on the hilltop.

A white cloud of shrapnel, first one and then several more, appeared above the hill.

I slowly moved upwards; beside the path, in a ditch, lay the infantry cover.

Officers sat in a group, smoking and talking. I lit a cigarette and started asking questions; it turned out this hill was indeed an important point of our position, and it was very likely the Japanese would spare no shells to dislodge us from this place. As if to confirm the words of my companions, the shrapnel clouds appeared more and more frequently above the hill, and the hiss of the shells became increasingly audible.

Our artillery worked nonstop. In addition to the roar of the cannons, the air was filled with the constant buzzing of passing shells.

I walked around the hill to see our infantry lying in the sorghum and trenches. Climbing further up the path, I rounded a protruding part of the hill and saw a white cloud very close by and, at the same time, heard the unpleasant rustle of shrapnel bullets. I retreated behind the protrusion. Looking down, I saw a soldier without a cap and with a bloody cheek crawling about a hundred paces away. My first instinct was to rush forward and help him. As I moved forward, two soldiers emerged onto the clearing, grabbed him under the arms, removed his pack and cartridge belt, gently led him aside, and disappeared into the sorghum.

I stood still, not daring to step out from behind my cover. There were many white clouds of shrapnel; now, they were flying further beyond the hill.

Soldiers began to emerge onto the clearing, first one by one, then in twos, and finally in groups; they hurried by, many carrying two or three rifles, and there were lightly wounded men who, clutching their wounds, hastened to the dressing station. A group appeared carrying a stretcher. I saw an officer lying on it, his head thrown back, one leg unnaturally positioned; the soldiers carried him carefully, their faces concentrated and serious; the sun was scorching, everyone was covered in dust, and the soldiers' shirts were marked with wet sweat patches.

After standing for a few minutes, I returned and reached the dressing station along with the lightly wounded, who formed a continuous stream.

Remarkably, among the crowd of wounded, I didn't hear a single moan except for words like "Easy, brothers" or "Keep in step"—nothing more. We had to walk at least two kilometers; shells hissed overhead the entire time. I wondered what the wounded felt, risking being wounded again or killed on their way to the dressing station. For a healthy person, this road was very unpleasant. I took several photos of groups of wounded who looked at me puzzled. While photographing them, I felt a strange sense of awkwardness and shame before these heroes in gray. It seemed my place was not here with a camera but at the front with a rifle in my hands.

By the roadside stood a large tent marked with a red cross, clearly visible from afar; around it lay many stretchers with men in various poses.

Empty stretchers, stained with blood, were being cleaned and carried back to the hill for new casualties; behind the tent stood wagons and horses. The tent flaps were lifted; everything was visible: the wounded, nurses, doctors, and a priest.

I approached closer; a newly brought stretcher with a wounded man was just placed down; the doctor and two nurses quickly undressed him to the waist.

The wounded man raised himself and propped himself up on his hands on the stretcher. There was nothing noticeable on his bare torso, just a small red spot on his back; the bullet had gone through, the wound was not dangerous, and there was almost no blood. The wound was quickly washed and bandaged, and then they moved on to the next in line. There were different kinds of wounds. I won't describe them in detail; I'll just say that the wounded barely groaned and bravely endured the bandaging, the doctors worked with great diligence, and the nurses treated the suffering soldiers with heartfelt care.

A little away from the tent, I saw a row of figures covered with greatcoats on the cut sorghum. I approached closer—they were dead. My heart sank sadly as I looked at this row of men lying there. My hand involuntarily removed my hat, paying the last respects to the brave men who had laid down their lives on the battlefield.

It was already around 4 p.m. Fearing the convoy might leave without me, as the village had also come under shell fire, I hurried back to the village. On the way, I met a dragoon and learned from him that the convoy was preparing to move out. I quickened my pace and, arriving at the square, learned from the convoy commander that we could not leave because if the Japanese took the hill, we would have to leave immediately, and thus, everything had to be ready to move at a moment's notice.

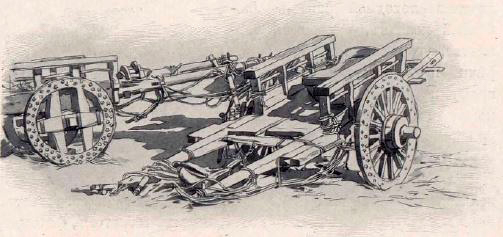

After checking on my Isida, I ordered her to be saddled and went to get some food from the soldiers' cauldron. Nearby, a damaged gun with a broken carriage was being transported; a field forge was set up, and I watched them repair the gun. The soldiers, with rolled-up sleeves, quickly removed the gun from the limber; the forge flared up, hammers clanged, and within half an hour, the gun was repaired.

The evening was falling, and to the sound of artillery fire was added the crackle of rifle fire; the volleys grew louder and closer, and infantry units began entering the village and occupying the fangs.

It was evident that the enemy was drawing nearer. It was already completely dark when the convoy commander finally received the order to retreat. Everything started moving, and the usual hustle and confusion began until the convoy lined up on the road. During this, there was an unpleasant delay, the reason for which we, being at the front, did not know for a long time.

The priest, the veterinarian, and I rode ahead, followed by the cash box under an officer's guard and a platoon of dragoons. Then, about 50 wagons of the convoy formed a very long line, especially since the narrow road was inconvenient.

Having barely managed to leave the village and reach the turn onto the main road, we received an order to stop because one of the wagons had broken down, and the load needed to be transferred to other wagons.

We stood at the road's turn; behind us, in the ominous darkness, the volleys of rifle fire, interrupted by artillery salvos, crackled. The flashes of shots in the night gloom flickered like lightning. Our horses were restless, and it took great effort to keep them in place. A clear shout of "Hurrah" echoed. It was evident that our forces were either repelling an attack or launching a bayonet charge. The shots drew closer. In the dark, the noise and clatter of wheels were heard on the road, and then a battery trotted by, obviously retreating along the same road. Our situation worsened: we realized that we wouldn't be able to get onto the main road until all the artillery with their wagons and parks passed, and behind us, they were still dealing with the broken wagon. Finally, the issue was resolved, but we had to stay put because the artillery occupied the entire road, and there was no way to squeeze in the convoy.

The stamping and snorting of horses, the clatter of wheels, the noise of a large mass of people on one side, and the crackling of shots, getting closer by the minute, on the other, made our wait unbearable. The horses were frantic, and to top it all off, I lost my pipe and couldn't find it in the dark. There was a ditch on either side of the road, and the horses kept falling into it, getting even more agitated.

Retreat from Liao-Yang to Mukden

Tired of waiting, I crossed the ditch and tried to make my way through the sorghum; I probably went too far to the side, especially since there was no way to navigate the dense sorghum thicket.

After riding half a verst in the sorghum, my Isida shied away from a dark figure that appeared suddenly. I first thought it was a Japanese soldier, but it was one of ours. "Where are you going," he said, "the Japanese are in that direction." I had just begun to ask him about the road when the crack of a volley nearby and the whizzing of bullets through the sorghum forced me to stop talking. Isida turned in the opposite direction and galloped, breaking through the sorghum.

I didn't know where I was going and tried to restrain the horse and calm her down. The sorghum whipped at me and tangled around my legs.

Finally, Isida slowed down, and the sorghum became less dense; riding was easier, and within a few minutes, I emerged onto the main road, where, to my great pleasure, I saw our convoy, barely moving along the road and surrounded on either side by a disordered crowd of infantry.

It was evident that they were retreating. The units were mixed; officers were not visible, and soldiers, nervously excited by the battle, were sharing their impressions on the move. Several stretchers were being carried, bearing the severely wounded, and one was a dead soldier. Still, the others didn't want to leave him behind and continued carrying him to give him a proper burial.

A group of soldiers was helping a wounded officer but was unwilling to leave his unit and walk. Tattered and torn, the flag flapped in the twilight, surrounded by a denser group of men. All this, overtaking our convoy, kept moving and moving or sitting down by the roadside to rest. Occasionally, officers on horseback tried to restore order. Here and there, single shots rang out from careless handling of rifles, and stray bullets whistled past.

RETREAT (FROM SYKVANTUN TO MUKDEN)

Morning. The terrible night was over. Golden streaks appeared on the horizon; the sun was about to rise. I looked back, and in the bluish haze, the end of our convoy, slowly crawling along the ashen-gray road, was disappearing. The road had become significantly wider, allowing the wagons to move in two rows. Along the edges of the road, in the sorghum, and along the paths, solitary figures of infantrymen and riders were making their way.

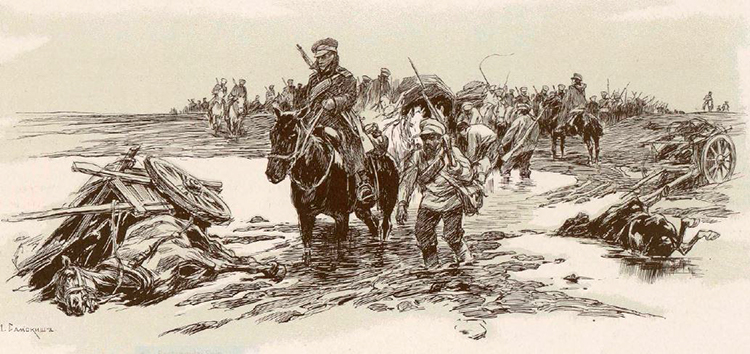

Ahead, towards the rising sun, flowed an innumerable crowd of people like a broad river. As far as the eye could see, this river of people, horses, wagons, and artillery moved along the road, rising over hills and descending into valleys.

All kinds of arms, in the most diverse uniforms, were mixed on this path. The sun rose, and its rays slid over the heads and weapons, enlivening this thousand-headed crowd with bright, golden glimmers. It seemed impossible to escape from it, as the elemental force carried all these individuals forward. The impression was that only a miracle could turn this crowd back or stop it.

I wanted to stop and rest after the terrible and anxious night, but how? How could I escape from this stream? And if I did, how could I rejoin it with a convoy stretched out over almost a verst?

The convoy commander, Shevchenko, approached me on a beautiful white horse. We lit up, talked, and shared our impressions. "When will we rest?" I asked him. Instead of answering, Shevchenko spread his arms, pointing to the crowd surrounding us.

But we, the horses and the convoy people, were exhausted by the anxious night and needed rest.

We turned off the road and set up camp at a suitable spot. It was around 2 o'clock when, at a turn in the road where it was possible to leave the stream of people, we sharply turned aside. Among the crowd's curses, who were delayed by our turn, we emerged into a field planted with beans.

It was hard to believe we had freed ourselves from this forward drive and could stand still while the stream of people rushed past us.

With an indescribable pleasure, I dismounted from my good Isida and handed her over to a dragoon. I loosened her girths, knowing it would take another hour before the soldiers freed the horses from their saddles.

In no time, the convoy was arranged in a quadrangle at the edges of the bean field; feed was ready: the beans were gathered and given to the horses; the dragoons quickly lit small fires from dry sorghum, and the kettles began to boil.

They prepared tea, and everyone noticeably revived. The convoy kitchen smoked enticingly, attracting everyone's attention. Still, there were those who, having fallen onto a bundle of beans, slept the sleep of the dead, arms outstretched and exposing themselves to the scorching rays of the midday sun. Finally, lunch was ready, and everyone eagerly dug into the food.

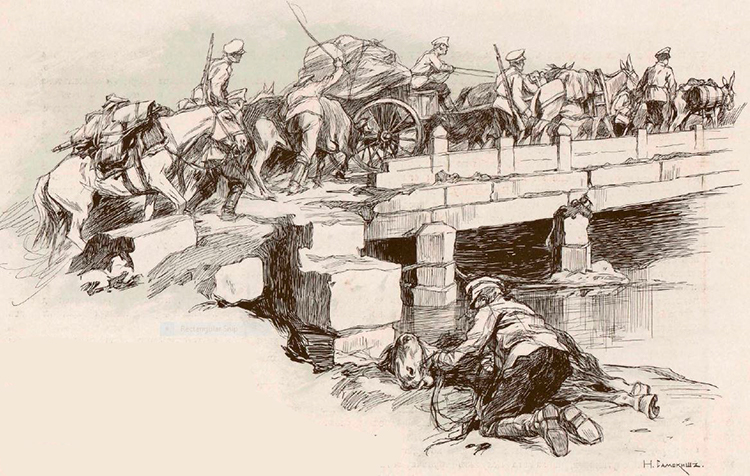

Crossing the river under fire

The simple stew, seasoned with canned goods, seemed like the pinnacle of culinary art. After eating, I thought I would fall asleep, but my nerves evidently couldn't calm down so quickly, and feeling no need to sleep, I went to the main road, drawn to the sight of this unprecedented crowd, this mass—almost without gaps—of moving living beings.

What scenes!

The always overloaded Chinese carts, laden with regimental or officers' belongings and harnessed in the most impractical way with a mass of ropes connecting four or five horses, were the cause of confusion, disorder, and often dramatic collisions with wagons, two-wheeled carts, artillery boxes, and guns. People suffered, but the horses suffered most; here and there, poor animals fell, never to rise again. If possible, they were dragged to the side, but if not, the convoy rolled over their corpses as there was nowhere to turn.

The air was thick with swearing, occasionally interrupted by the crack of breaking axles and the shouts of officers trying to restore some order.

There were also disputes among commanders over who should have the right of way, who should go ahead, and who should stay behind; it seemed like a matter of life and death as if it made a difference whether one arrived an hour earlier or later. Everyone was in a hurry. Watching all this, I wondered what would happen if even a small detachment of resolute men struck this crowd from the side! The consequences of such a surprise were unimaginable: this crowd would have annihilated and trampled itself.

Fortunately, this did not happen, and nothing occurred that could have led to panic and catastrophe. Later, I learned that all measures had been taken to prevent the enemy from disturbing our retreating troops and convoys.

I returned to our camp. It was already evening, and it was decided to move further ahead before nightfall.

The two-wheeled carts were quickly hitched up, and the horses, refreshed by the rest, were saddled. The convoy approached the main road. It took considerable effort to merge into the general line and not get separated. It required many arguments, shouts, and whip cracks before everything was sorted out, and we began to crawl forward—there was no other way to describe our movement.

Twilight descended, and the crowds got lost in the mysterious gloom; soon, lights from the resting troops glimmered along the sides of the road. We walked for six hours and couldn't find a suitable place to turn off the road for the night.

The convoy commander suggested I go off-road with a few dragoons to find a suitable clearing for the night. After struggling through people, wheels, and harnesses, I reached the edge of the road, crossed a ditch, and carefully surveyed the area. I rode through sorghum and millet fields, looking for a turn onto the main road.

After riding for half an hour, I finally saw a road suitable for turning off for the night.

I held back my horse and waited for our convoy; my men had gotten lost somewhere in the dark, but I wasn't too worried about it, as it seemed easy to find our convoy. Standing by the main road for twenty minutes, carefully watching the passing crowd, I started to worry; our convoy was nowhere to be seen. I waited longer—still nothing; finally, I rode towards it parallel to the main road. I had to ride along a narrow path, constantly bumping into individual soldiers walking the same path; both my horse and I risked running into almost invisible bayonets in the dark, but everything turned out fine. I rode two versts ahead—no convoy; I felt desperate, realizing it was impossible to find it in the dark and confusion.

I quickly returned to the previous spot and moved forward again, knowing the convoy couldn't overtake me since I was moving faster. Therefore, if I rode a good distance ahead, I could rest, and the convoy would catch up with me; that's what I did.

Returning to the road I had previously found, I saw that it was entirely occupied by artillery: guns, limbers, and horses in harness stood motionless in the middle of the road, with the tired crews lying on the ground in the dust. Everyone was asleep; I didn't see a single awake soldier. They slept the sleep of the dead, their heads often lying under the wheels of the guns and the hooves of the horses. One slight movement of the horses forward, and the heads of the sleepers would have been crushed, but the horses were asleep just like the people; everything was exhausted and needed rest.

The sight of this sleeping battery further influenced my decision to stop and rest. A little off the road, I saw fires and tents; it was a sappers' camp. I rode up, and the sentry asked me who I was and why I was there. I told him I had been separated from my convoy and wanted to rest, requesting to be allowed into the camp where my horse could be safe and I could sleep peacefully. After consulting with him, the sentry called the guard leader and allowed me into the area where the tents were set up. I unsaddled my horse, tied her up, and went to make tea.

With pleasure, I lay on a mat by the cheerfully crackling fire and began rubbing my knees, which had gone numb from the eight-hour ride. I was extremely grateful to this kind young man for his hospitality. I instantly fell asleep after drinking tea and stretching out on the mat.

I woke up suddenly and immediately looked at my horse, Isida, peacefully dozing under a tree. It was just morning, and it was quite light. From Isida, I shifted my gaze to the road. To my great surprise, I saw a group of riders on gray horses among the dark crowd of moving people. Could it be our dragoons? (The Nezhinsky dragoons' horses are gray.) I stared intently, and indeed, it was our convoy.

I quickly saddled Isida, jumped into the saddle, thanked my gracious host, and trotted towards the convoy.

They were very glad to see me. The convoy couldn't move forward for three hours because broken-down carts and wagons blocked the road. The officers and the priest had also rested by the roadside, waiting for the path to clear.

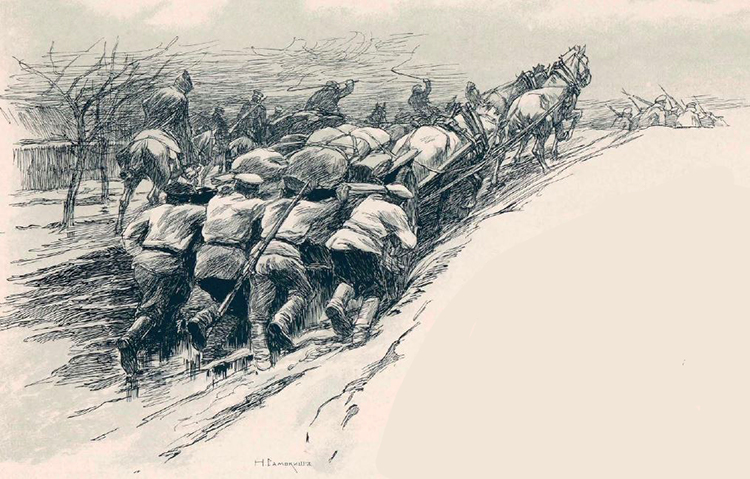

During the stop, an order was given for the convoy to switch to another road parallel to the Mandarin road, allowing the troops to move faster. We crossed the railroad tracks, and the scenes at the crossing were indescribable. The ground was soaked from the drizzling rain, covered with watery dust. I felt thoroughly soaked: saddle, reins, my Isida, my clothes, everything was wetter than water; I was afraid to take the camera out of its case to avoid damaging it in the terrible dampness. On the ascent, the horses slipped, fell, and rolled down, overturning the carts surrounded by figures coated in sticky Manchurian mud, hardly recognizable as humans. This continued for several hours until it was our turn to slide, fall, and get covered in mud up to our ears. Finally, we made it to the other side of the tracks.

The road became wider and free of ditches, which was very pleasant, especially in the dark, when the ditches were most treacherous, causing carts to overturn and people and horses to fall.

Everyone was soaked and tired from crossing the railroad. It was decided to camp for the night before dark; any shelter from the rain was out of the question. We turned off to the side and settled on the first clearing on the wet, soaked ground, laying bundles of wet sorghum under us so as not to lie in the water accumulated between the field's furrows.

There were no trees or dwellings for a long distance around; lighting a fire was out of the question, and thus warming ourselves with tea was impossible; everyone was in the worst spirits. The priest set up a makeshift tent and settled in it with the convoy commander, inviting me to crawl under the wet canvas, but I preferred to stay in the open air.

The night was cold; I covered myself as best I could with my wet cloak and fell asleep, resting my head on the saddle. I must have slept for a long time, as I woke up when it was already quite light. The rain had stopped, but the puddles had increased overnight, and my underwear, clothes, and boots were all wet. I was shivering as if I had a fever; to warm up, I quickly got up and, since everyone was still asleep, started walking briskly away from the camp, wanting to restore some warmth in my body through movement.

About a verst and a half from our camp, I saw smoke. I headed there. Upon approaching, I saw an artillery camp with a small fire in the officers' tent where a kettle was boiling.

I approached the tent and saw several officers having tea. I entered, explained who I was and how I ended up there, and asked for tea. My request was immediately granted, and I gladly dipped dry bread into the refreshing drink, feeling a pleasant warmth spread through my body.

I couldn't stay with my new acquaintances for long; the convoy might set off, and I could lose it again, which would be very unfortunate as my horse might also leave with the convoy. I thanked them for their hospitality and quickly returned. Everyone in our camp was already awake; people stretched their cold limbs and shivered from the morning chill.

The sun rose, and everyone cheered up. Somewhere, they found an abandoned crate on the road, which served as firewood for us. We made tea and warmed up some canned food. The sun began to warm and dry us.

Around 10 o'clock, we set off and walked along the railway tracks. We walked all day and, by nightfall, reached the Yantai station, where we camped near the station. The night passed more peacefully, and we could see the station lights and the trains whistling. In the morning, I ran to the station, hoping to buy something, but my hopes were in vain; I only bought a little tobacco and was glad of it, as I hadn't smoked for a long time, having lost my pipe and used up all my tobacco. I returned to the camp, shared my purchase with my companions, and received a pipe from the priest, so I smoked, making up for the time without a pipe and tobacco.

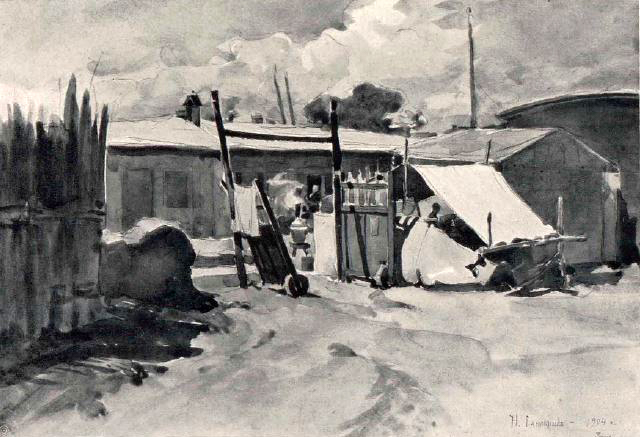

Settlement in Mukden

From Yantai, we moved again along the Mandarin Road to Mukden, rejoining the stream of people and reaching a river with fairly steep sandy banks by noon. There was no bridge, so we had to ford the shallow river with a fast current.

It was a beautiful sunny day, the sky was blue, and both banks of the river, covered with crossing and already crossed troops, provided me with many wonderful scenes.

Giving my Isida to a dragoon, I walked around on foot, photographing picturesque groups. Infantry, artillery, and cavalry were fording the river and climbing the opposite sandy banks. There was a lot of sunlight, movement, and sparkle. To capture some groups, especially the artillery entering the water, I crossed the river several times, stopping in the middle to catch beautiful moments.

My boots were full of water, but that didn't bother me: I was fascinated by the scene's beauty and forgot about my feet, for which I paid with a severe cold. The convoy also crossed the river, I mounted my horse, and we moved forward.

After several versts, the blue ribbon of the Hun River appeared in the distance. We approached the bank by the bridge; here, the convoy stopped, waiting its turn. Again, I had the opportunity to photograph picturesque groups of Chinese fleeing to Mukden with their wives, children, cattle, and household belongings. They were crossing the Hun River by swimming. The Chinese were escaping from the Japanese, as our enemies did not treat the local population very humanely.

The carts were loaded with sorghum tied with ropes; on top of such rafts sat women, children, and the elderly; young Chinese men, completely naked, shouted and drove the horses and mules into the water, swimming for a while in the middle of the river, continuing to shout and whip the horses until they reached shallower areas. The carts floated well on bundles of sorghum, like on pontoons. There were many very amusing scenes, but everything ended well, and amid laughter and squeals, the Chinese crossed to the other bank. Meanwhile, the troops were crossing the bridges built on pontoons; there were three such bridges. We were directed to the one our unit was to use, and the convoy moved towards the middle bridge; here again, there was a delay: we had to wait our turn, which was not soon. Tired of waiting, I swam across the river and waited for our convoy to reach the other bank. The commander managed to be cunning and squeeze our convoy ahead of its turn; although he had to endure a quarrel with other commanders, the convoy soon found itself on the other side, and we moved towards Mukden, the towers gilded by the setting sun. Before reaching the city, we set up camp and began our tea.

I looked at the familiar city with pleasure, hoping to find the much-needed rest and comfort there.

N. Samokish

For two weeks, I hadn't undressed, changed my underwear, or washed for two or three days at a time; there was no time for that. My clothes were worn out and torn to rags. I hadn't shaved or had a haircut for three months. The severe itching all over my body indicated that I had picked up some unwanted companions, the usual companions of a campaign, and to top it all off; my boots only looked like boots from the top; there were no soles at all, and the tops were worn through from prolonged riding.

Lying under a tree on the green grass, I looked at the nearby Mukden tower and thought that I had earned a rest. Now, I could sleep under a roof every day, get rid of the rags on me after the campaign, and put on fresh underwear and clothes.

SHAHE

After a month of campaign life, I returned to Mukden but didn't recognize it. At the beginning of July, I left a flourishing city: everything was green, and there was cleanliness and order everywhere. Music played during meals at the officers' club, the station, and the streets were filled with the elegantly dressed crowd of the ruler's staff officers, and the shops near the settlement were bustling with trade. Now, it was a picture of complete devastation: everyone who could be hurrying to get out of Mukden to Tieling and then to Harbin; houses were being abandoned, passing troops were burning wooden buildings for fuel, and the shops in the settlement were all boarded up and abandoned, as everyone thought Mukden would be evacuated. Only at the station was there any trade, where one could get a poor-quality cutlet for 1 ruble or a bottle of champagne for 15 rubles. The Greek buffet manager had no qualms about setting high prices—a hundred poor-quality cigarettes cost 5 rubles, and so on—he knew everything would be bought, no matter the quality.

Houses without doors and with broken windows looked desolate and grim. A Red Cross bivouac stood by the ruler's house on the main square. I found shelter in the press censorship office for correspondents with my acquaintances, Colonel P. and Captain T. They also lived in a bivouac and were ready to leave Mukden at any moment. I slept on a pile of hay thrown in the corner of the room, but even that seemed like paradise after sleeping in the rain during a wet August night on the soggy sorghum. Here, I could have more hot tea and a simple daily meal than in March.

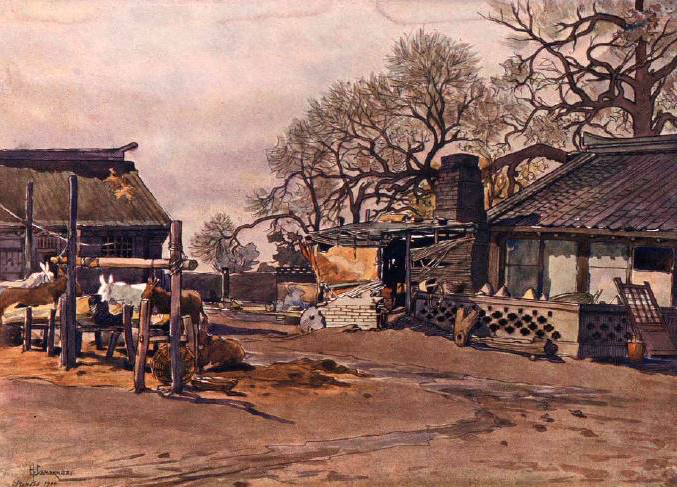

Chinese house courtyard in Mukden

Having settled into my accommodation, I decided to stay in Mukden for a while to organize my materials and my completely ruined outfit. The first thing I did was buy boots at the Economic Society, and then in the Chinese city, I bought a warm Chinese jacket and padded trousers, as the cold was quite noticeable in the evenings and early mornings when I went out to sketch. The passing troops provided plenty of material, and the landscape in its autumn attire was magnificent.

A week later, my hosts left for Harbin, and I stayed in their quarters, but not for long. My accommodation was taken over for an intelligence department where prisoners were interrogated; they gave me a small room at the station, but I was evicted from there as well because my room was needed for something else (in wartime, everything changes extraordinarily quickly). They gave me a room in the settlement, in the apartment of reconnaissance officers under the commander-in-chief. I lived in this little room for quite a while, and since it was already very cold at night, with frost, I set up a metal stove. While the stove was burning, it was warm, but as soon as the fire went out, the stove instantly cooled, and the heat escaped through the numerous cracks, so I kept warm mostly with hot tea.

There were no major actions on our army's front and flanks; the Japanese were inactive after Liaoyang. Our troops were consolidating and fortifying positions, with talk of an offensive. I lived relatively peacefully in Mukden, doing my work leisurely and waiting to move to the front line. During this time, I made several sketches of captured Japanese soldiers and attended their interrogations. One night, I woke up to the distant sound of cannon fire; the next day, it became known that our troops had gone on the offensive, and fighting was happening along the entire front. The continuous sound of cannons, clearly audible in Mukden, confirmed this. I hurriedly packed my small baggage and took the first train to Shahe, where our center and battle raged. At the Mukden station, I already encountered the wounded. Taking a freight car, I traveled to the Sujiatun station (the trains went no further). Getting off the train, I walked along the tracks towards the sound of gunfire and the columns of smoke from burning villages.

Captured Japanese dragoon