Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

THE SEVASTOPOL ALBUM

by N. Berg, 1858

Interior of a Battery of the 3rd Bastion

Introduction

Nikolai Berg (1824–1884) was born in Moscow. His father later relocated to Siberia, where he held the post of Chairman of the Tomsk Provincial Administration. In the early 1830s, the family returned to Moscow, and upon completing his gymnasium education, Berg enrolled in the Historical-Philological Faculty of Moscow University. The outbreak of the Crimean War prompted him to resign from his position at the state bank and travel to Sevastopol, where he served on the staff of the commander-in-chief as a translator and took part in the Battle of the Chernaya River. The culmination of his involvement in the Sevastopol campaign was the publication, in 1858, of Notes on the Siege of Sevastopol (a translation currently in progress), accompanied by the Sevastopol Album (comprising 37 illustrations), which is presented below for the reader’s attention.

The Sevastopol Album by N. Berg, 1858

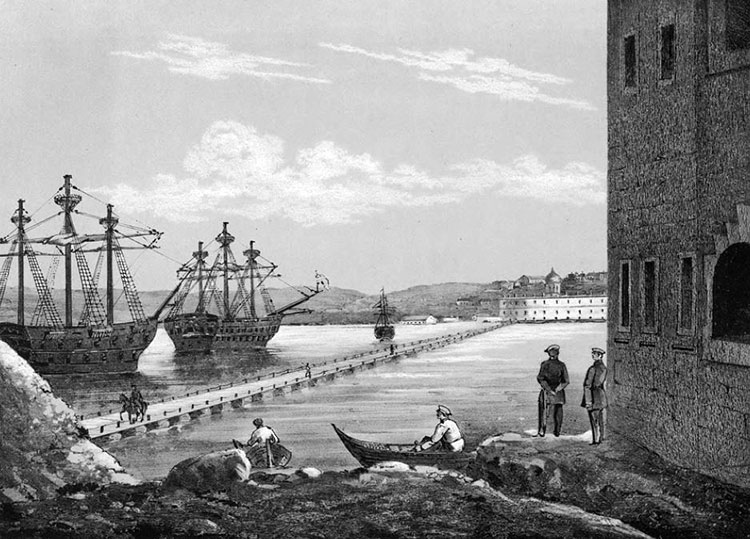

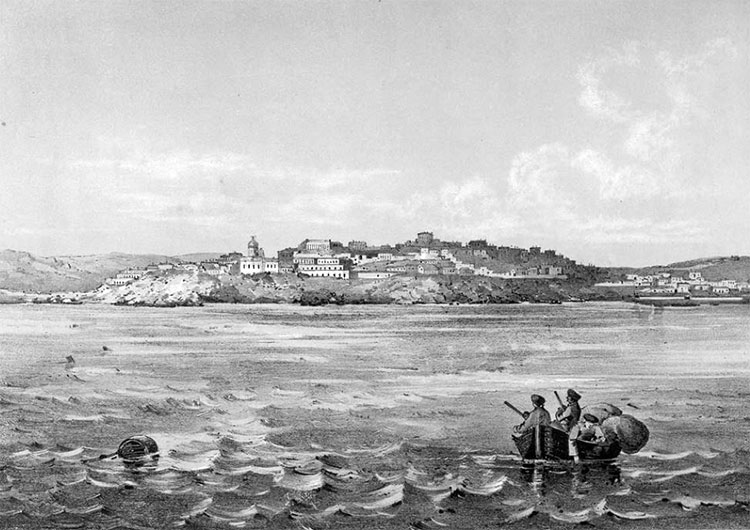

1. SEVASTOPOL

The drawing depicts Sevastopol at the moment when it had two bridges. Closer to the viewer is the smaller bridge across the Southern Bay, built in April 1855 on pontoons, replacing the one previously located there on tenders which were sunk by cannon fire from the English batteries on Green Hill during the March bombardment. The first bridge was built in September 1854, shortly after the enemy’s landing. Next to the bridge shown in the drawing, on the far side, the masts of two sunken tenders are visible sticking out of the water. The shore on this side of the bridge is part of the Ship Settlement. Beyond the bridge, to the left, lies the Southern Side of Sevastopol. The two-story building standing highest of all is the library. To its left is the building with columns — the Church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church on the right, not far from the shore, is the St. Michael Cathedral. The long building on the very promontory is the Nikolai Battery or Barracks. From there, a large bridge leads to the Northern Side, ending at the base of the Mikhail Battery. At the far end of the Northern Side, to the left, is the Konstantin Battery.

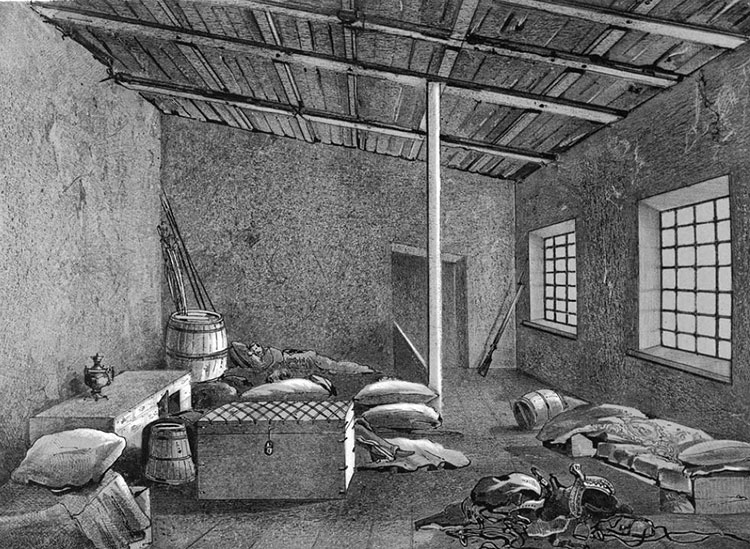

2. INTERIOR OF THE POST STATION ON THE NORTHERN SIDE OF SEVASTOPOL

This station was located in one of the stone barracks, not far from the hospital. One could say it was the first building encountered by anyone arriving on the Northern Side from Bakhchisarai. The depicted room is cluttered with various items: chests, suitcases, saddles. In the left corner, oats are heaped up, and on them officers sleep, having come from the bastions. Their sabers rest on a barrel; a few Cossack lances are nearby. Behind a trunk, on felt bedding, another officer is sleeping. There is no ceiling: the roof rafters are plainly visible.

3. THE ODESSA INN

This was the name given to the tent of our military sutler Alexander Serebryanikov. It was nearly the only place on the desolate Northern Side where one could grab a bite. It was made from sailcloth. You can see hanging reef points — small ropes used to shorten sails in strong winds. The Odessa tent stood about 200 fathoms from battery number 4, facing the Hen Ravine.

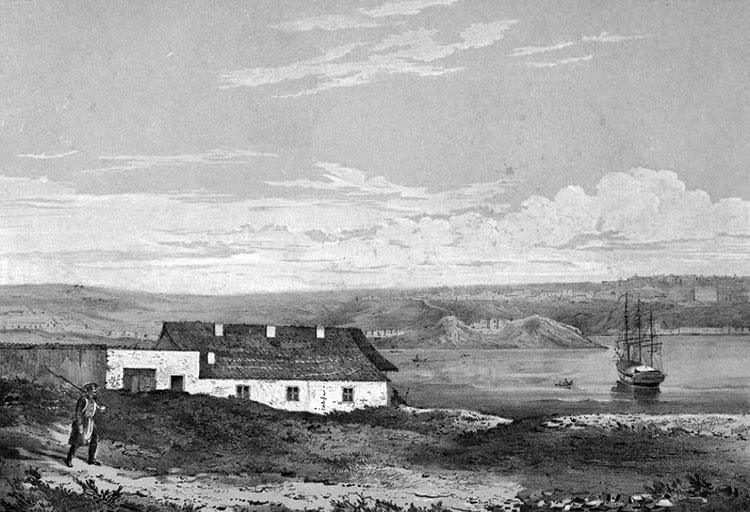

4. THE COTTAGE OF COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF PRINCE MENSHIKOV ON THE NORTHERN SIDE OF SEVASTOPOL

This was a small cottage on the very shore of the bay, near the Hen Ravine. It stood apart from all the other buildings. In the distance, the Southern Side of Sevastopol is visible.

5. ST. MICHAEL CATHEDRAL ON THE SOUTHERN SIDE OF SEVASTOPOL

It stands on the first half of Catherine Street if a viewer walking from the Grafskaya Wharf to the 4th bastion. During the siege, we conducted funeral services here for three admirals — Kornilov, Istomin, and Nakhimov — and for all officers who fell in Sevastopol. The cathedral suffered very little from enemy fire: one or two bombs hit it, along with a few cannonballs and shell fragments. The construction had not yet been completed, and so scaffolding can be seen around the dome. These remained throughout the entire siege and after. Only recently was the cross installed. To the left of the small new chapel adjoining the cathedral, also unfinished, part of a stone barricade is visible — a sort of embankment across the street. Several such barricades were built at various points in the city in case of enemy incursion. — The tower beside the cathedral belonged to the Admiralty; it had a clock, which was torn out by the French.

6. THE MONUMENT TO KAZARSKY

Captain-Lieutenant Kazarsky, commanding the 18-gun brig Mercury, cruised near the Bosporus during the last Turkish war. On the morning of May 14 (1829), he sighted several Turkish ships, two of which immediately gave chase and began overtaking him. One was a 110-gun ship flying the flag of the captain-pasha, and the other a 74-gun ship. Seeing no way to escape, Kazarsky convened a war council of his officers, at which the navigator, lieutenant Prokofiev, was the first to propose blowing the ship up. This was agreed upon. They resolved to defend to the last and then, falling onto some enemy vessel, ignite the powder magazine — for which a pistol was prepared and placed on the capstan. At first, Mercury suffered only from pursuing fire, but was soon caught in a crossfire. From the pasha’s ship, Kazarsky was called upon to surrender. He responded with fire from all his artillery and small arms. A desperate firefight ensued. Mercury withstood a three-hour-long, vastly uneven battle, and forced the opponents to retreat. For this feat, Kazarsky was promoted to captain of the 2nd rank, awarded the Order of St. George 4th class, and named an aide-de-camp. In addition, he and the entire crew received a lifelong pension, consisting of double pay. Kazarsky died in 1833, holding the rank of captain of the 1st rank, at the age of 36, and was buried in Nikolaev. A year later, a monument was erected to him on the Southern Side of Sevastopol, not far from the Grafskaya Wharf, on an elevated site where a boulevard bearing the hero's name was located. The monument is made of local white stone. At the top is an ancient trireme cast in iron. The bas-reliefs are bronze. One of them depicts Kazarsky’s face. All this survived completely intact, except for a few minor damages to the railings, as shown in the drawing.

7. INTERIOR OF AN OFFICER'S DUGOUT AT THE 5TH BASTION

This was a small underground room belonging to Lieutenant Markov, where one could barely turn around, but no bombs could penetrate. It was warm in the autumn and winter days, when rain and wind above were piercing. On the left is the owner's bed; on the right, a stove; under the ceiling a sail is stretched to keep dirt from falling.

8. INTERIOR OF A CORNER OF THE 4TH BASTION

This is the right-facing corner, nearest to the enemy’s approaches, which at the time I made the drawing, were about 60 fathoms away. Inside, several dugouts and a powder magazine are visible — the largest mound. On the farther face, shielded cannons are shown. On the right face there are also cannons, though they are not visible behind traverses — only the ramrods can be seen. On the traverses sandbags lie, from behind which riflemen fired.

9. UNDERGROUND ROOM OF CAPTAIN MELNIKOV AT THE 4TH BASTION

This was a niche within one of the mine galleries of the bastion, at a depth of three fathoms. The walls, due to dampness, were lined with felt and carpets, and an ever-boiling samovar stood on the table. To the left, on a small stove, the owner’s drawings and books were piled.

10. PLACE WHERE ADMIRAL KORNILOV WAS WOUNDED ON MALAKHOV KURGAN

It was not far from the tower. At the spot where he fell, struck by a bomb fragment in the abdomen, a cross made of cannonballs and shells was laid out, which remained for a long time, nearly until the end of the siege. Near the dugout on the right, the admiral received his first dressing.

11. KONSTANTIN BATTERY

In the foreground, a small portion of the Nakhimov Battery is visible, with a low parapet made of gabions and fascines, covered with earth and lined at the bottom with stones. The Konstantin Battery is in the background, beyond the bay. In the far distance, on the horizon's edge, a cape is visible, behind which lie several bays, including Kamysh.

12.

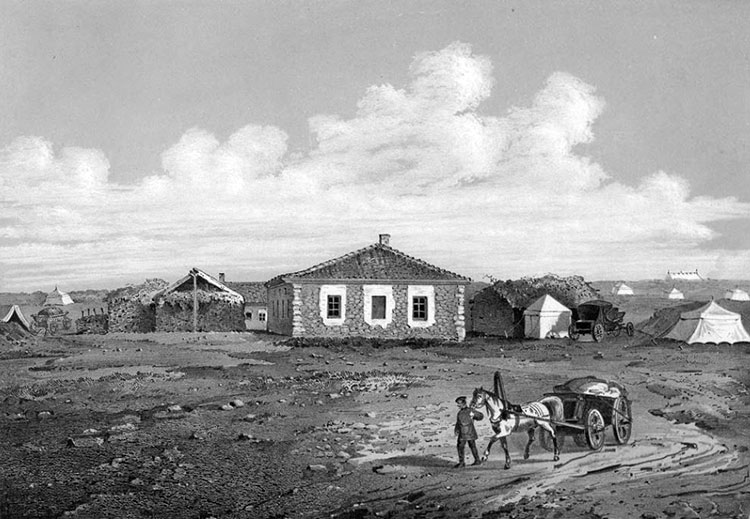

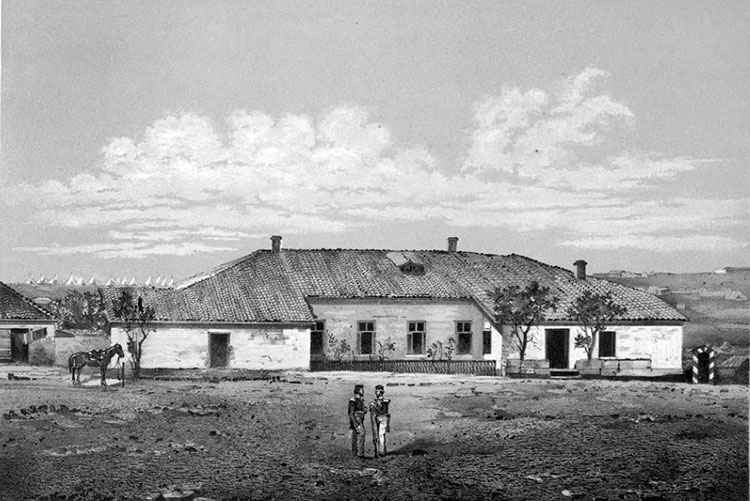

COTTAGE OF COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF PRINCE GORTCHAKOV IN THE INKERMAN CAMP

This was a small stone cottage that formerly served as a postal station on the road from Belbek to Sevastopol. When the 4th Corps arrived in Crimea (in 1854), Corps Commander General Dannenberg lived in this cottage. Here, the plan for the Battle of Inkerman was conceived. On October 23, 1854, the column of General Pavlov’s troops, consisting of six regiments with their artillery, passed by this cottage; but few of them were destined to see it again. Later, General Liprandi, then commanding officer of the 12th Division, lived here. In May 1855, the Commander-in-Chief, Prince Gorchakov, moved in. Next to the cottage on the left was a wattle canopy, under which the Prince dined with his adjutants on hot days. Behind this canopy is a two-window cottage that housed the chief of staff. On the right — a canopy, a tent, and the carriage of General Vrevsky. In the distance, on the horizon, the large tent of the Main Duty Station is visible, which, along with the surrounding tents, is shown in the next drawing.

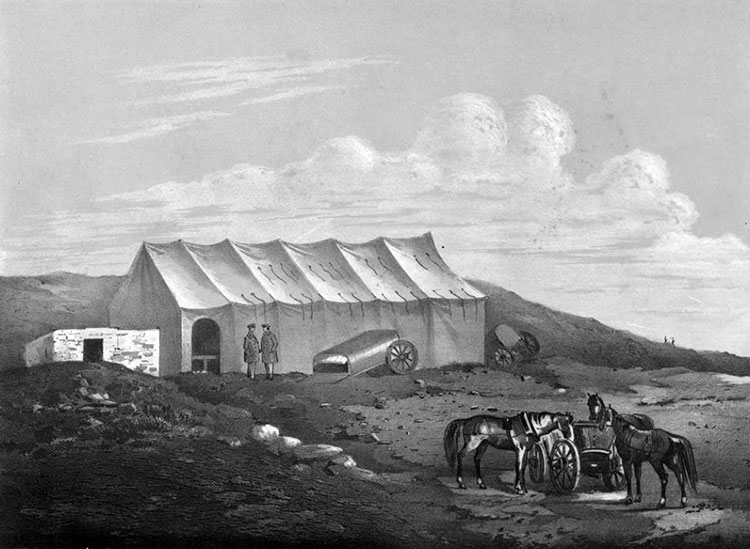

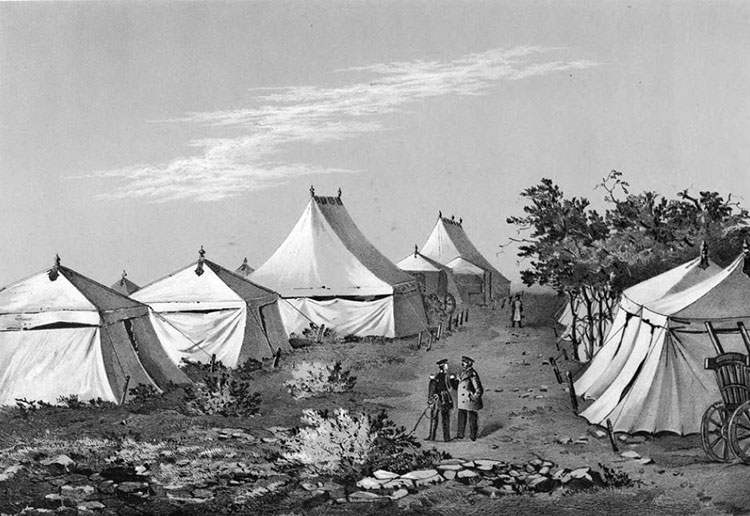

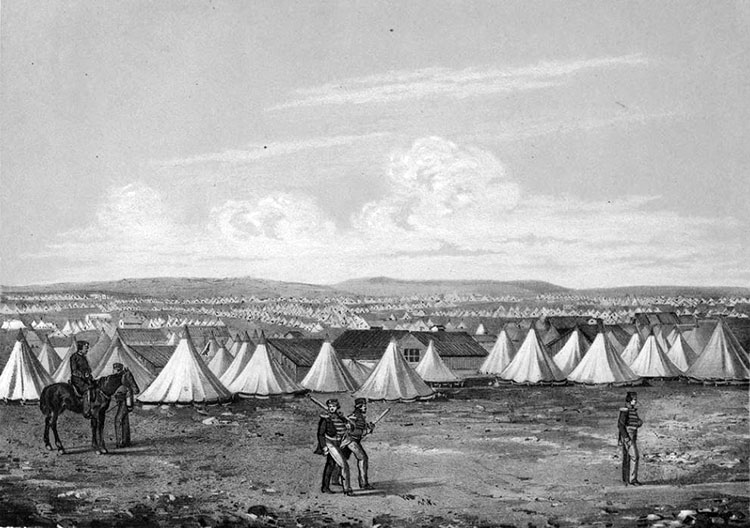

13. TENTS OF THE MAIN DUTY STATION IN THE INKERMAN CAMP

This was the center of the extensive operations of the staff. The space between the tents on the left and those on the right formed one of the main streets of the camp. In the first large tent were the 4th and 5th departments; in the second, of the same size, were the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd. Between them, in a tent behind a wagon, the head of the 4th department worked — simply called the treasurer. Orders and various items belonging to the 4th department were kept in the wagon. A bit further on the money chest stood, under a special canopy. The tents of the officers serving on the duty staff were around. One of the tents on the right was enclosed with felled trees and brushwood, as protection from the heat.

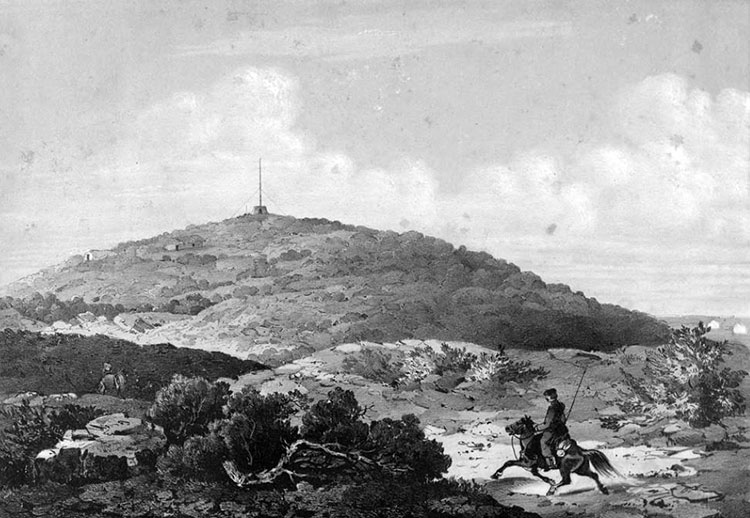

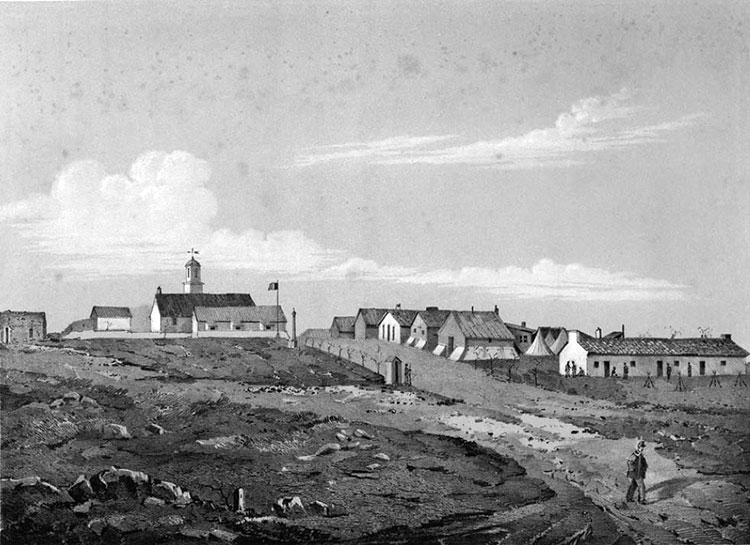

14. INKERMAN LIGHTHOUSE OR TELEGRAPH

This was one of the heights, a verst from the Main Staff camp. From this lighthouse, signals were sent with flags to the Main Staff and also to the Southern Side, concerning enemy movements. On the summit, the dugouts of officers monitoring the lighthouse gleamed white.

15. COSSACK BIVOUAC ON MACKENZIE HEIGHTS BEFORE THE BATTLE OF AUGUST 4

This depicts part of our general camp before the battle on the Chernaya River, namely the Cossack section. Officers of the Main Staff, as well as Cossacks and gendarmes attached to the staff, camped together. Each arranged accommodation as best as they could. Those with access to a tent pitched one. The Cossacks sheltered under canopies made from lances, over which cloaks and greatcoats were thrown. This bivouac adjoined the tents of the 6th Corps staff, stationed on Mackenzie Heights, not far from the road from Bakhchisarai to Sevastopol and Balaklava. In the foreground is the tarantas (carriage) of sotnik Popov, and to the left, his canopy made from Cossack lances.

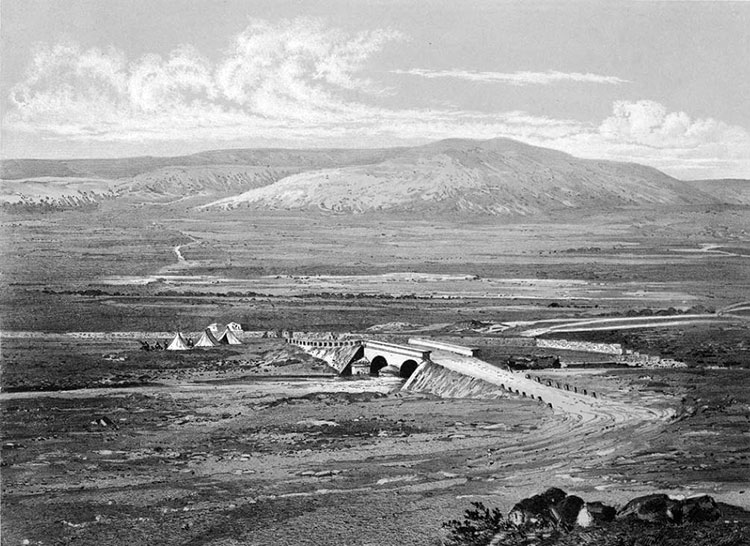

16. BRIDGE OVER THE CHERNAYA RIVER

Before the outbreak of hostilities, the road from Bakhchisarai to Sevastopol normally passed over this bridge. On the left, on this side of the river, there once stood an inn owned by landowner Revilotti, which existed until the end of 1854. It gave its name to the bridge in French military bulletins. Who hasn’t heard of Pont de Traktir? Sometimes, the very battle on the Chernaya was referred to by them as Combat de Traktir, even though the inn had no longer existed by then. It seems part of its dismantled walls was used as the foundation for the barricade the French erected beyond the bridge. It is visible in the drawing. Nearby are their guard tents. In the distance, the Fedjukhin Heights gleam white, which our 12th Division ascended during the battle of August 4 (1855), under intense canister fire. The French afterward inquired which regiments could advance so steadily under grapeshot and recorded their names. These regiments were the Azov, Odessa, and Ukrainian. It is said that there once was much greenery and various fruit trees near the bridge. Now, only a few small bushes have survived.

17. BRIDGE FROM THE SOUTHERN TO THE NORTHERN SIDE OF SEVASTOPOL

It extended from the Nikolai to the Mikhailov batteries. In the foreground to the right, part of the latter is visible. — It was one of the most remarkable pontoon bridges ever constructed for the transfer of troops and was built with extraordinary speed: it begun in the very last days of July (1855) and completed by mid-August. On August 15, the Day of the Assumption, after a liturgy, it was consecrated and opened. It consisted of six sections, or 86 pontoons, with a total length of 430 fathoms and another 20 fathoms of wharfs. The roadway was three fathoms wide. Despite the strong swells in the bay on August 27, during our retreat, the bridge held firm and served with glory: a 50,000-man army crossed it in complete safety. After the crossing was completed, the bridge was immediately detached and then pulled to north shore.

18. MAIN STREET IN BALAKLAVA

To the right are the old Balaklava buildings, to the left—new English barracks. In the distance the old Genoese fortifications are visible, which inspired Mickiewicz to write the sonnet Ruiny zamku w Balaklawie. The small Balaklava Bay is not visible, hidden behind the buildings on the right. The masts of ships appear above the rooftops.

19. HEADQUARTERS OF THE ENGLISH ARMY

This was the house of General Bracker, on his estate, six versts from Sevastopol, on the road to Balaklava. At various times, three commanders-in-chief of the English army lived here: Raglan, Simpson, and Codrington.

20. HEADQUARTERS OF THE FRENCH ARMY

It was located not far from the English headquarters, just over a 0.7 mile away, on a hill to the right of the road when traveling from Sevastopol to Balaklava. Everything shown in the drawing was newly built by the French. In the center is a sort of boulevard, lined with trees. To the left, under a flag, is a small wooden house belonging to Marshal Pélissier. It was entirely painted gray, except for the foundation, which was left white. Behind it is a stone house where the marshal dined. This house was white with a red roof. Behind it, a wooden tower protrudes, which held the clock taken by the French in Sevastopol from the Admiralty Tower. On the right are the houses of the marshal’s top subordinates. Most of these houses were wooden and painted the same gray color. Only those belonging to the marshal’s staff, or outsiders with direct business with him, were allowed to walk along the boulevard past them. The long stone building on the right is the main guardhouse.

21. ENGLISH CAMP

It differed from ours only in the shape of the tents and in that the tents were mixed with barracks. The French under Sevastopol had exactly the same pointed tents, supplied to the allies by the Turkish government in November 1854, six thousand in total.

22. MALAKHOV KURGAN, VIEW FROM THE SOUTHERN SIDE

Across the bay, right on the shore, are visible the naval storehouses, which served as dressing stations during the siege. Further up, beyond the wall, are the houses of the Ship Settlement, and finally Malakhov itself—a small elevation cut through with trenches. Did you imagine it so insignificant and low-lying? Yes, this is the very hill that cost the French so dearly and earned Pélissier the title of Duke. The tower is not visible because at that time it had been almost entirely destroyed.

23. RUINS OF THE NOBLEMEN’S ASSEMBLY HOUSE WHERE THE MAIN DRESSING STATION WAS LOCATED

It was a large stone building, a few steps from the Grafskaya Wharf, marking the beginning of the right side of Catherine Street. Here, during the siege, the renowned Pirogov worked with his students. In the center, in the main hall, beds for amputees were arranged. The amputations themselves were carried out in the room to the left, where there are two windows. Just around the corner, in the distance, the hill with the boulevard and Kazarsky's monument can be seen. In the room to the right, which also had two windows, the attendants for the patients were housed, and a samovar was always boiling. Next to this room, a little further on, are the remnants of a broken fence and gate that led to the boulevard. The Assembly House burned during the fire of August 27 and 28, and the ceiling collapsed inward.

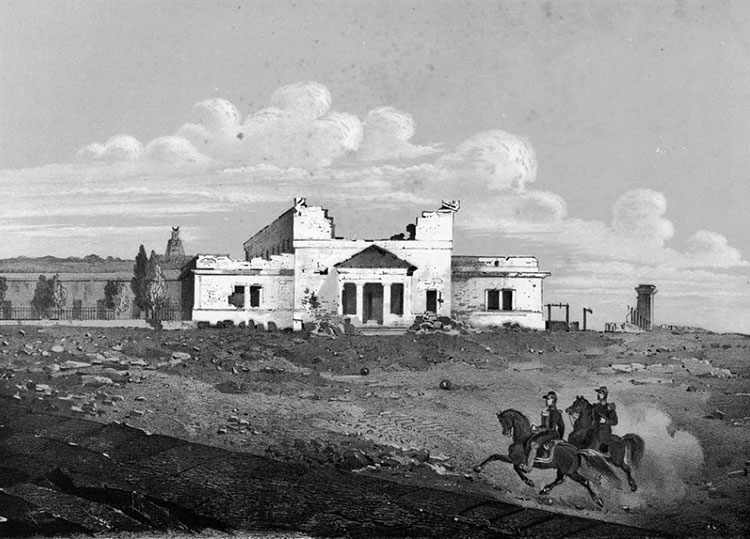

24. RUINS OF THE PALACE OF EMPRESS CATHERINE

It was a one-story stone house on a platform between the Grafskaya Wharf and the Nikolai Battery. During the siege, it housed a hospital. The house survived until the final day, but during our evacuation of Sevastopol, it was damaged by fire. The lifeless ruins long stood like a pile of stone, often struck by our shells from the Northern Side. After the peace was concluded, this dead mass of stone came to life again: the French attached a kind of pavilion to the ruins, where they opened a café restaurant, a convenient and profitable establishment in such proximity to the Wharf. Everything that landed at Grafskaya Wharf immediately saw the inviting sign. Here, our sailors and soldiers who came from the Northern Side were often served. The owner would step out onto the porch and silently beckon them with his hand. In the middle of the pavilion, below, a gray square not covered with planks is visible: this is the remnant of the stone balcony that adjoined the house. One ascended it from both sides by stairs. But the former and seemingly main entrance was at the back, from the inner courtyard.

25. CATHERINE STREET

This is, so to speak, the middle of the street. To the left are the ruins of Krasilnikov’s house, where, at the beginning of 1855, Count Osten-Sacken occupied in the upper floor. Below were Karaite shops and the well-known confectionery of Johann, familiar to every Sevastopol resident, located directly across from the tree. To the right is Schneider’s hotel; a little further along is Thomas’s hotel. Beyond it is a large two-story building: again, the shops of the Karaites. At the top, the building shaped like a pantheon is the Church of Saints Peter and Paul.

26. RUINS OF THE SEVASTOPOL THEATER

At the end of Catherine Street, one came upon this building. The theater suffered greatly even during the siege: it stood almost adjacent to the 4th bastion, which was located to the right, on the elevation where the boulevard used to be. It was impossible to walk across the square past the theater because of the swarms of sharpshooters’ bullets flying there, and for this reason a trench was dug on the side, which people would descend into about 200 fathoms before reaching the theater.

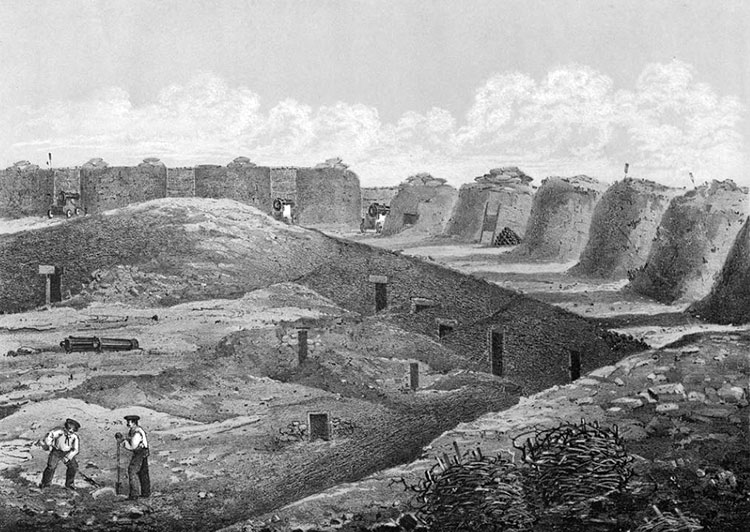

27. THE FOURTH BASTION FROM THE ENEMY'S SIDE

Who would believe that these are the remains of that impregnable 4th Bastion, which withstood the siege for so many months and held out with glory until the end? The enemy never crossed its parapets, although for nearly half a year it was the main focus of the French: they approached to within thirty fathoms and still could do nothing. Countless mines were laid beneath these ramparts, but with our skilled countermines and camouflets (explosions directed toward the enemy), we forced them to abandon underground warfare. Many fierce skirmishes took place before these sunken merlons, which by then no longer resembled anything at all! I ask the reader to look at drawing No. 8 to compare what it was and what it became: this is the very same corner, first shown from the inside, and now from the outside.

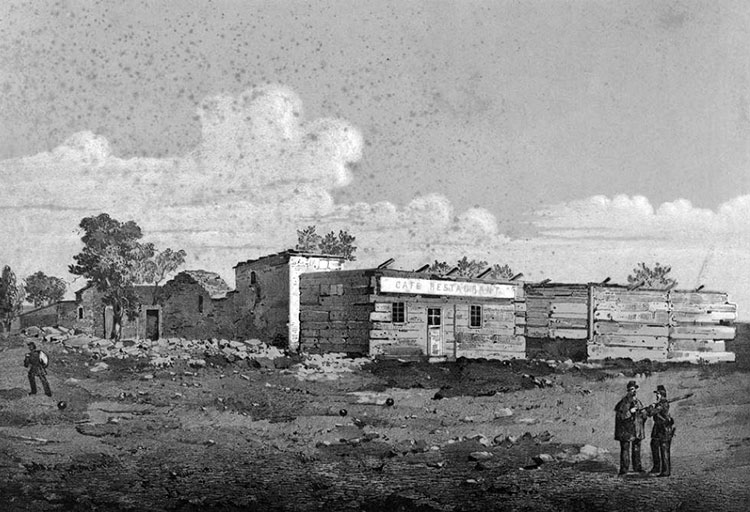

28. THEATER AT KAMYSH

Everyone knows about Kamysh and likely remembers that it had a Rue de la Gloire—an inevitable street in every French military town of this kind. The reader may have seen depictions of it in various illustrations. Opposite this street, across the square, stood the theater, built at the wish of the Emperor of the French, for which a certain Chauveau was sent to Kamysh—he who had amused French audiences in the deserts of Africa with countless theaters. Chauveau was a true genius of theater-building. Wherever he appeared, a theater would soon follow. He crafted them quickly, in pure campaign fashion. For the construction of the Kamysh Theater, he was given only three weeks. To save time and materials, Chauveau came up with a trick: since a theater hall should slope downward toward the stage, Chauveau dug part of it into the earth, completed the rest with planks, and plastered and painted everything from top to bottom. There was no way to detect his makeshift architectural cunning. I could barely believe it, even when he confessed it to me himself. The theater was excellent and held 1,200 people. The best seats and orchestra stalls cost 5 francs; the parterre—2 francs. Actors and actresses were brought from Paris and performed quite decently—for Kamysh. Every evening, crowds gathered around the theater; guards stood with rifles at the doors and in the corridors; and this brightly lit, visible-from-afar place had something alluring, teasing—just as all lively, crowded spectacle venues do. One couldn’t help but want to buy a ticket. At first, performances were given every day, but later two days a week were excluded—Mondays and Fridays. Playbills were posted near the doors, printed at the headquarters of the French army. Chauveau, for fun, would label them Imprimerie impériale.

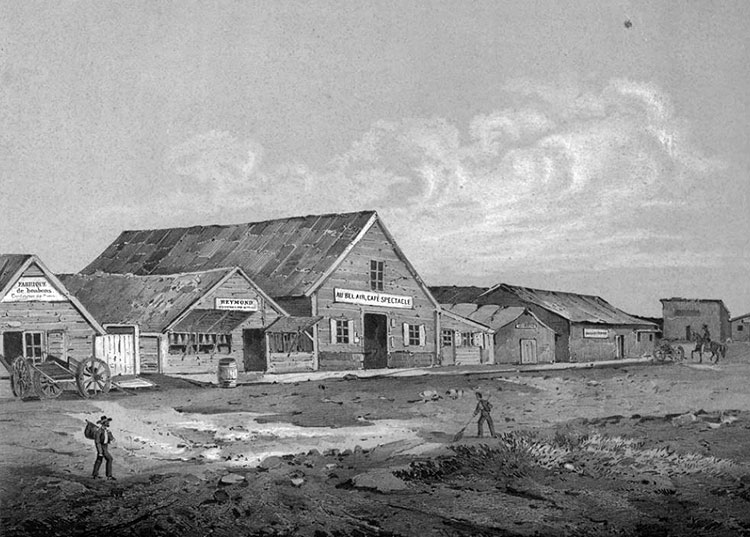

29. NAPOLEON STREET IN KAMYSH

This was the second street to the left of Rue de la Gloire, another inevitable street for the French. It was just as wide as the first. There was a hotel for foreigners—a large one-story building, or shack, if you will. In this building, under the sign Au bel air café-spectacle, people usually gathered after the performance, but they didn’t stay late—until about midnight. Then the staff would begin extinguishing the lamps, one by one, as the tables emptied; guests gradually left, and the café-spectacle and all of Kamysh would fall into silence and darkness. Playbills were posted there too, near the doors. All these buildings—not quite homes, not quite shops—looked summery and glittered briefly. This was the Makaryev Fair of the Army of the Orient, where one could buy anything, find a cheerful circle in a cozy, lit room, its walls papered in bright calico, the ceiling covered with chintz... tables all around, white cloths, gleaming glassware; paintings on the walls; shelves lined with bottles... one could get so lost in it all as to think oneself truly in a city.

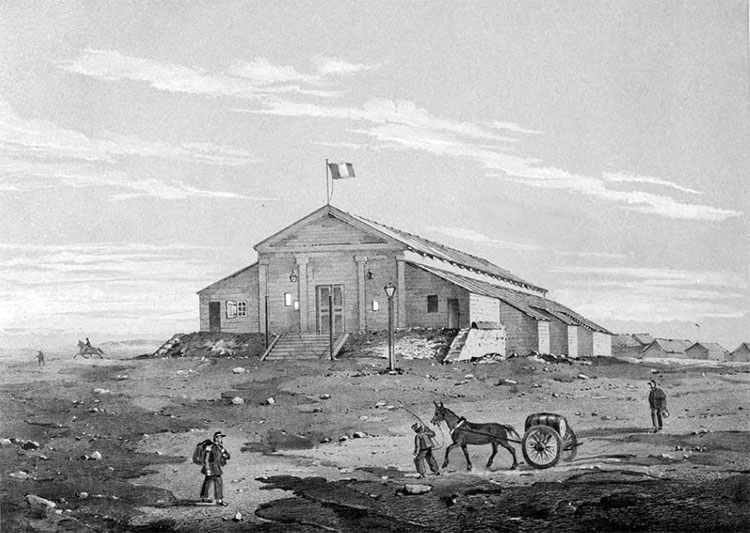

30. THE FRENCH CHURCH IN KAMYSH

It stood on a platform to the right of Rue de la Gloire. It was a wooden structure too. On the corner, near the church, a guard always stood.

31. BATTERY NO. 22

It was built on the promontory between the Dry and Northern Ravines, shortly before our evacuation of Sevastopol. Its appearance was rather original, and I sketched it for that reason—to show the full variety of Sevastopol’s batteries. In the distance, beyond the bay, the Southern Side of the city is visible.

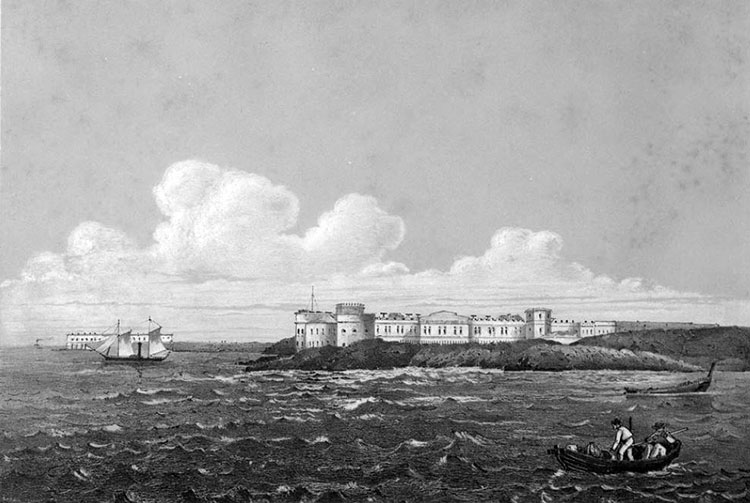

32. THE MIKHAIL AND KONSTANTIN BATTERIES

Here are more batteries! But what do they have in common with No. 22? These are already buildings, or fortresses—the kind one usually imagines batteries to be. The true, characteristic Sevastopol battery, the kind that defended the city for eleven months straight, will be shown a bit further on.

33. RUINS OF THE MALAKHOV TOWER

This is the foremost part of the Malakhov Kurgan. In front of the tower—of which only the lower tier remains—there was once a platform, the largest on the entire hill, nicknamed Devil’s because it was under such heavy fire. On the day of the assault, in the remains of the tower that the reader now sees before him, a small group of our soldiers held out—just 30 men—with Lieutenant Yuny, Second Lieutenants Danilchenko and Bogdzevich, and two conductors of naval artillery: Dubinin and Venetsky. Our men returned fire for several hours, and the French could do nothing, because the entrance to the tower was blocked by a postern and a deep pit, which served as a communication tunnel with the mines. MacMahon, commander of the 1st Division of the 2nd Corps, which stormed Malakhov, ordered the tower to be surrounded with fascines and set on fire, to smoke our men out, as they did with Arabs—but then he realized that the fire might reach the powder magazines and ordered the fascines to be extinguished. The French placed a cannon opposite the entrance to the tower and began firing grenades at us. Our men managed to douse the first grenade with water, but the second exploded and wounded half of the defenders; one of its fragments broke the icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker hanging in the corner and extinguished the lamp burning before it. This was a bad omen for Russian soldiers. Then Yuny sent Conductor Venetsky as a parlementaire and surrendered. This was already around seven o’clock in the evening. — After taking the hill, the enemy set up a telegraph on the tower the very next day, with a hut for observers. When I sketched this drawing (in April 1856), the telegraph was already gone; only the hut remained, with a guard, for whom a Russian sentry-box had been dragged up to the top.

34. SOUTHERN SIDE OF SEVASTOPOL AFTER THE CONCLUSION OF PEACE

Drawn in April 1856 from the steamship Andii, which was then anchored near the Mikhail Battery. At that time, the Nikolai Battery, which previously stretched along the entire shore from the Southern Bay to the Artillery Settlement, no longer existed.

35. INTERIOR OF A BATTERY OF THE 3RD BASTION

This battery was drawn immediately after we left the Ship Settlement. Here is a true Sevastopol battery! Scattered gabions, fascines, planks, logs, canister charges, barrels, ropes. A damaged cannon with a broken muzzle has been pushed aside; another one already stands in its place, but its shield has been torn off by a cannonball... to the right is the dugout of the battery commander. Everything looks destroyed; it seems there’s nothing of value here! And yet this battery was more impregnable than a stone one, especially with defenders like those who stood at its guns. A stone battery is difficult to repair: you need finished, hewn stone, cement, and many other things; but here—if a merlon was destroyed, a traverse flattened—the repair was at hand: within an hour or two fresh gabions were set up, bags thrown in place, a new parapet emerged—and the cleaned cannon resumed pounding the enemy!

36. PART OF THE ALEXANDR BARRACKS AFTER THE EVACUATION OF SEVASTOPOL

In the foreground are the hospital buildings that adjoined the barracks. The barracks themselves are visible in the distance. One day (in April 1855), a bomb hit them and passed through every floor, from the roof to the basement, where a woman with two children was sleeping at the time. Of course, under four ceilings, death did not even enter her dreams. The bomb rolled under the bed and exploded there, one fragment piercing two ceilings above. The woman was severely wounded, and the children were killed on the spot. All these buildings were located near the bastions, under heavy enemy artillery fire, and therefore looked almost equally ruined long before the city was surrendered.

37. DUGOUT OF THE HEAD OF THE 3RD DEPARTMENT

This was one of the luxurious constructions of its kind. The usual dugouts of department heads looked outwardly like ordinary soldiers’ shelters; in a word, they were exactly the same as the one shown in drawing No. 35.